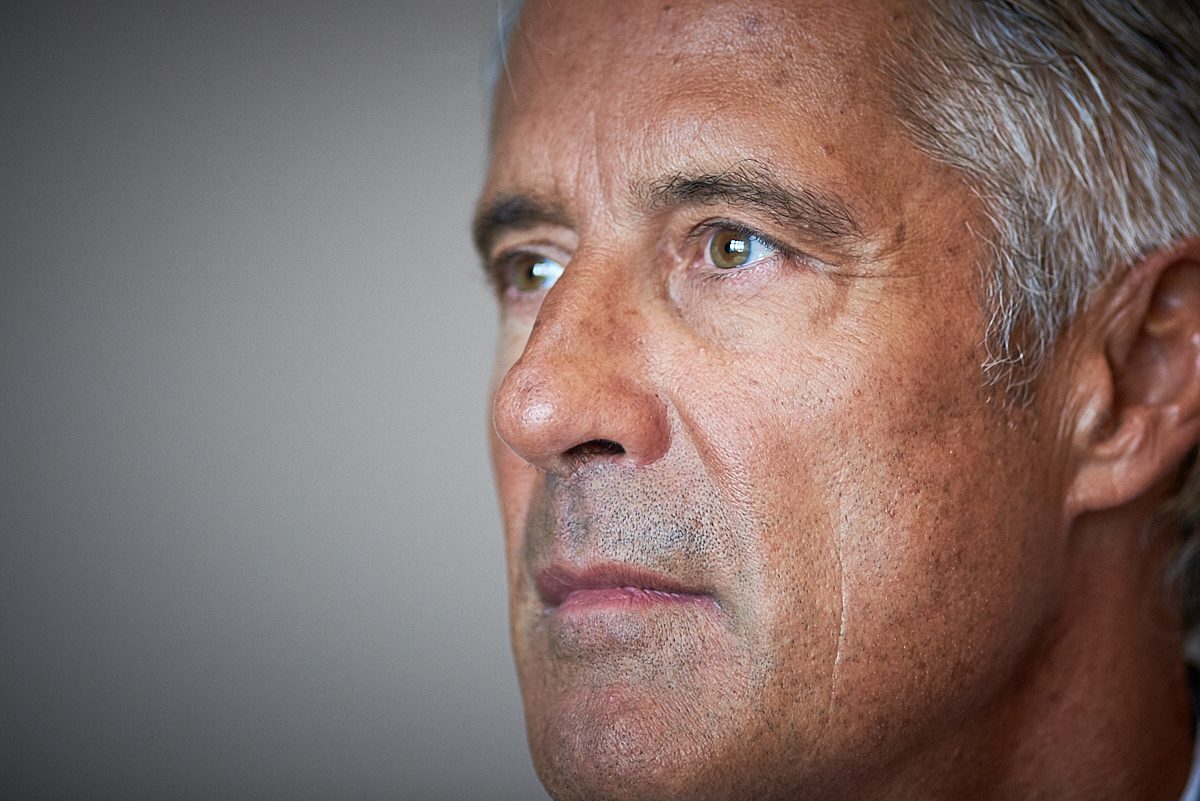

“No, I don’t want to be a Federal Councilor.” Walter Thurnherr, 55, Federal Chancellor of Switzerland

As the “eighth member” of the Federal Council, Federal Chancellor Walter Thurnherr acts an advisor to the Swiss federal government. He does his job so well that he’s being considered as a successor to Doris Leuthard, a departing federal councilor for the political party CVP (Christian Social Party).

He’s said to be a visionary, a doer, well-connected, willing to compromise and smart as a whip – and funny to boot. It’s no wonder that politicians (across all parties) and the media are full of praise for this man. Wouldn’t the logical consequence of this be a place on the federal council? Thurnherr declines immediately: “I like being the go-between who isn’t always in the limelight.”

Who is this physicist from the Freiamt region in Aargau, Switzerland? Who, after a detour to Moscow, has lived with his wife and two grown-up children high above Lake Thun (or “Lake Thurnherr”, as he jokingly tried to teach his children when they were still small) for 20 years. Who reaches across partisan divides like no one else. Who loves to relax with a book on math or physics and can’t stand people who don’t have a sense of humor.

After a mountain walk from Niederhorn to Habkern (canton of Berne) lasting almost four hours, we sat down to a hearty lunch and talked about humor, the Higgs boson, and feeling at home.

“Living in the midst of this stunning natural landscape can’t be taken for granted.”

“Living in the midst of this stunning natural landscape can’t be taken for granted.”

Anna Maier: Would you describe this area around Lake Thun as your home?

Walter Thurnherr: Yes. Although I grew up in Freiamt (canton of Aargau), for 20 years, this area has been the center of my world. I see these mountains almost every day. I feel at home here.

During our walk, you often stopped and pointed here and there: “Oh look, how beautiful!”. Don’t you get used to your everyday surroundings at some point – no matter how stunningly beautiful it is?

No, I don’t think that will happen to me. Look around you! It looks like something from a calendar in the ‘60s! The blue sky, the white snowy mountains, the lake. Nature makes a stunning impression here.

I think it has something to do with the fact I lived abroad for several years and can appreciate what Switzerland has to offer.

About twenty years ago, in Sigriswil – at a viewpoint – I met a man who was sobbing. I asked if I could help him. It turned out he had grown up in a so-called “Plattenbau”, a housing project in Leipzig, Germany. As he looked out across Lake Thun towards the mountains, it hit him: “This view is so incredibly beautiful! I could have grown up here, too. But chance, or fate, intended otherwise.” Then he suddenly looked at me sternly and said: “You can look at this every day: I hope you appreciate it!”

That got to me a bit. And it’s true. Living in the midst of this stunning natural landscape can’t be taken for granted.

Twenty years ago, you were a stranger in Sigriswil, too. Why did you choose this place to settle down with your family?

It was by chance. We were looking for a house near Thun, where my wife works. It had to be easy to get to Bern and the federal government, too. And, of course, it was, is and remains a simply stunning place.

What sets the people of Sigriswil apart?

In my experience, the people here aren’t any dumber, smarter or prettier than anywhere else. But people from Sigriswil are direct. They’re familiar with each other and say what they think. I appreciate that.

“Particle physics is a perfect party pooper.”

“Particle physics is a perfect party pooper.”

Before you settled in Sigriswil, you were in the diplomatic service in Moscow. As a committed physicist, you might have been expected to go into academia. Why didn’t you?

Well, I noticed relatively early on that theory wasn’t the only thing I wanted in my life. Although I find theoretical physics and mathematics absolutely fascinating, they’re not the only things that spark my interest. You can have a great chat about particle physics with two or three people. Everybody else flees when you get started. It’s the perfect party pooper (laughing).

There are a lot of other things I’m interested in. Such as our history, what happens in our world. What’s going on in other countries, in foreign policy.

I happened to see this poster at the University of Bern. The Federal Department of Foreign Affairs was looking for candidates for what was known as a ‘concours’ for the diplomatic service.

By pure chance, I passed.

By chance? You’re teasing.

No, I really wasn’t expecting them to take me. After all, it’s usually mostly lawyers, historians and economists who are interested in a career in diplomacy.

I think they found it funny that for once, a physicist had a go at applying, so they probably didn’t ask me very tough questions. They were delighted I knew when the First World War happened (smiling).

“I was in Moscow at the end of the Cold War, when the system collapsed.”

“I was in Moscow at the end of the Cold War, when the system collapsed.”

So, you suddenly found yourself on a plane heading toward Moscow. Did you know what you were in for?

No. Of course, I already knew a bit about Russia, but I couldn’t imagine then what life would be like on the ground.

I was lucky that I had a good ambassador who quickly gave me responsibility. He said: “Write political reports! Get on the ground, talk to people.” Early on, I wrote a detailed report on the political and social consequences of the reactor leak in Chernobyl.

And because a lot was happening in the East at that time, they read my reports in Bern. The whole Eastern Bloc was undergoing major upheaval: Ceaușescu was shot dead in Romania, the old conflicts were bubbling away on the edges of the USSR. Every week, the new press, emboldened by glasnost, were bringing more scandals to the surface.

“Look, this guy’s from Switzerland!”

“Look, this guy’s from Switzerland!”

And you were in the middle of it all. How did people approach you as a foreigner?

I was very well received. In 1989, you were really passed around if you came from the west: “Look, this guy’s from Switzerland!” That was an interesting experience.

What was your life like in Moscow? You probably didn’t speak any Russian when you got there, right?

I had Russian lessons from the very first week. I had to learn quickly when I was there, because at that time, very few Russians could speak a different language.

I also got my driving license in the Soviet Union. I’ve still got it. I took driving lessons with an instructor from Moscow. He didn’t just teach me how to drive. He taught me a lot of shortcuts, and introduced me to friends. That way, I got to know the people and the language quickly.

But of course: I was a stranger in a strange city. I had an official residence to myself.

And a driver?

No, I drove myself. I had a little Zhiguli I zipped around Moscow in. Back then there was hardly any traffic, but multi-lane highways.

In 1995, when I was sent back to Moscow a second time for a few years, everything had changed.

What was different?

There were much more traffic jams. And a lot more crime, too. People were disenchanted. In complete contrast to 1989, when most people greeted the end of the Cold War and collaboration, exchange and new consumer goods from the West with euphoria. In 1995, the economy was going downhill. In 1998, disaster struck. And the rapprochement with the West they had desired didn’t turn out the way many in Moscow had imagined.

“My mother still thinks I have too many pie-in-the-sky fantasies.”

“My mother still thinks I have too many pie-in-the-sky fantasies.”

You went back home. How had Switzerland changed?

In Switzerland, you can live an incredibly efficient life.

What do you mean by that?

You can get almost anything done quickly in Switzerland: going to the dentist, getting shoes repaired, having a key cut, fixing a car, buying a newspaper.

A few years ago, I had to re-tile the roof of our house and have the chimney renovated. So, I got up on the roof with a bricklayer, a roofer, a carpenter and a plumber. They looked around right away and arranged it: “Will you take a 6.5 here? That way I can pull right back there!” – “OK, then I’ll finish this level, so the plumber can take over in front.” – “Very good, then I’ll pull the bar up to the top!” – I didn’t understand a word, except that they knew what they were talking about. And in the end, the roof, the chimney and the new skylight were perfect.

These things really struck me when I came back. And we can be proud of them in Switzerland.

When you came back from Russia, you often went around wearing a “Cossack hat” in the winter. Were you homesick for a foreign land?

No, I just liked wearing it because it kept me warm. It was made from muskrat. In Moscow, everyone goes around with one of those. But it was stolen from me later. Sadly.

Let’s go even further back: when it came to your career, the thinking was actually very different. Your father wanted you to become an apprentice. Were your parents eventually proud of the more academic path you took?

You know, no one from my family studied. High school and university were a whole new world for my parents. They were rather skeptical about it. My father was a bricklayer, a foreman, a master builder.

Did he have his own business that you were supposed to take over?

No, he worked in a company as an employee.

My brothers also went to college later on. But for me, as the oldest, the question was asked, why should I go to high school, an apprenticeship would also be something… They got used to it eventually. They weren’t really convinced by theoretical physics, but it is hard to envision what it means, exactly.

On the walk, you told me a sweet story about your mother and how she asks whether they still need you in Bern.

Yes, she knows all about how silly I can be. Imagine someone like me in the Federal Palace (laughing)!

My mother would have been happy if I’d learned a manual trade. My parents always said: “A good tradesman is worth a lot” – and they’re right, too.

“I’m fascinated by physics, because it offers simple explanations for complex things.”

“I’m fascinated by physics, because it offers simple explanations for complex things.”

What was it like for you to misbehave?

Of course, my parents noticed that I wasn’t particularly skilled with my hands. It wasn’t hard to see. I took apart every radio I got my hands on and couldn’t put any of them back together again (laughing). The career advisor we asked in the end said that theoretical physics would probably be something I would like. And a few years later, I was actually really excited about it.

What excited you about it?

The fact that it offers simple explanations for lots of complicated things.

“I’m happy where I am.”

“I’m happy where I am.”

People say you’re smart as a whip. That you’re loyal, and very well-connected. What is it that makes you so popular? Virtually everything that’s written about you is positive.

What’s written is very short-lived. There may be a time when journalists write the opposite.

You were elected by parliament to the role of Federal Chancellor in late 2015 with an outstanding result of 230 votes. Presumably, you could also count on huge support in a federal council election. Wouldn’t that be the next logical step?

I’m not thinking anything based on the result. And no, I don’t want to be a federal councilor.

Why not?

I’ve always seen myself as more of a man of the administration. I’m happy where I am: I know the administration and the people who work there well and I also know what problems they face.

In my opinion, by the way, we have a very good administration. It’s sometimes made out to be worse than it is.

What’s good about it?

There are lots of very skilled and dedicated people who work there. Of course, mistakes are made. But we mustn’t shy away from comparison, either with major service providers or the administration in other countries.

Call the administration in another country. You’ll be lucky if they call back, and you don’t have to travel far for that. In Switzerland, your letters usually get answered. And a problem usually gets a sensible solution.

Federal Councilor Thurnherr also seems a sensible solution: there are few CVP (Christian Social Party) candidates for the Federal Council seat being vacated by Doris Leuthard who have the kind of cross-party connections you do.

There are plenty of candidates in the CVP. But Doris Leuthard hasn’t even stood down yet. Anyway, I find it rather strange when people start talking about successors before the councilor in question has even stood down.

Really? But it’s never too early to start talking about succession. That’s how it is in the private sector, too.

You’re right. But I’ll stick to it: there are plenty of other people who are up to the job. And I like being chancellor.

How important is the role of chancellor?

I think the chancellor is quite important (laughing). The role of the chancellor, let’s see:

Apart from the fact that they have a consulting role in many issues, they’re involved with all the political rights. Everything to do with initiatives, referendums, votes and consultations. They are also responsible for contact with parliament, federal council communications, the presidential service, security clearances, the language service and all federal publications.

Increasingly, more and more business is prepared by the general secretary convention. It is the highest coordinating body of the federal administration, which I lead. This is where compromises should be readied or technically challenging business that the federal council simply doesn’t have time for should be assessed. For instance, for IT projects – these can be vast, expensive projects.

“From whistleblowers to professional hacking: what’s been happening in recent years is creating uncertainty.”

“From whistleblowers to professional hacking: what’s been happening in recent years is creating uncertainty.”

Which brings me on to the topic of e-voting. What actually happened for you to suddenly find yourself confronted with the situation where you have to draft a bill by the end of the year? Is that really part of your job as chancellor?

Yes, it is. The federal chancellery has already been dealing with the issue of e-voting for more than 15 years.

It’s said that the issue of e-voting would be an overreach for you. A critique you’re really not used to.

Yes. It doesn’t come as a surprise, either. The things that have been happening in the last two or three years – from whistleblowers like Snowden and professional hacking of businesses to allegations of voting manipulation – are a concern, of course, and many people are asking whether they want or need e-voting at all.

And? Do we need e-voting?

All of a year ago, I had to answer to parliament as to why we weren’t making faster progress with e-voting. We were already saying back then: safety before speed. Safety is the main thing.

There were two motions then that wanted to force the cantons to introduce e-voting by 2019. We advised against this.

Today, it’s the other way round: some are saying it’s moving too fast. Now, I have to say: after 15 years and 200 successful attempts, you should be able to decide whether you want something or not.

Isn’t e-voting part of a path to the future we have to take anyway?

It’s a path that many cantons say they want to take. And I personally believe, based on our previous experience, that e-voting, with the enhanced security precautions we’ve required since July 1, can be pursued.

But this is a matter that should and will be decided upon by the lawmakers, or even the public. There are no personal emotions attached to it.

Where do you find a balance for your cerebral work?

I do a bit of jogging, read books on mathematics.

Isn’t that just a cliché?

No, reading something completely different is just the best thing for taking me out of everyday life.

What’s in these math books?

Fun things, like knot theory. These books are very well written now. They aren’t as boring as they were back in school.

And an incredible amount has happened in recent years. Like in cosmology or particle physics, with the search for the Higgs boson and what you can do with it.

“I’m not great at celebrating myself.”

“I’m not great at celebrating myself.”

If these matters still fascinate you as much as ever: wouldn’t you like to be there on the front line in research?

No. I have no regrets about taking a completely different path. But when something earth-shattering happens or is published in the field of physics, of course I take particular note of that.

They’d been talking about the Higgs boson for 40 years. And on July 4, 2012, it was discovered. In other circles, that might not be much of an event, but for a physicist, it was an important moment.

Speaking of important moments, we’re doing this interview two days before your 55th birthday. Is it a big day for you?

No.

Never?

It was important to me until I was about 11, when there were still plenty of presents.

Do you never celebrate? Not even the big ones?

Actually, yes I do. I celebrated my 50th.

What did you do?

Dinner with lots of people. I even arranged two parties. One with friends I know from the federal administration. And another with family. I put up a tent in the garden for that one. But apart from that, I’m not great at celebrating myself.

You’re very well connected. But it takes time, a lot of time, to cultivate contacts. How do you manage that with your tight schedule?

I’ve always particularly liked people who want to make something happen.

In the 30 years I’ve worked in the federal administration, I’ve met many people like that. And over time, I’ve also noticed that there are good people in business, too (laughing). Of course, you don’t always have the same amount to do with everyone, but you do see them time and again. Switzerland isn’t such a big place, after all.

You don’t need to see each other every week or every month, but every now and then. And if you’ve worked together well before, then more often than not, you can talk on a personal level. I appreciate that kind of communication.

“I don’t mind a situation escalating.”

“I don’t mind a situation escalating.”

You’ve said that you like people who want to make things happen. Don’t you feel like doing that yourself? From the outside, your position doesn’t seem like one where that’s possible.

You maybe see it less from the outside. But I can make things happen here and there.

As chancellor, I act as a link and an advisor, and that’s what the law says, too. And this link is necessary, because there are sometimes snarls in the administration or between parliament and the administration.

I’ve got good links to parliament. That helps in my position. And luckily, in Switzerland, we have a simple way of solving conflict: if you have imagination, and people really want it, you can find solutions. That goes for the administration, too.

Only sometimes, I am a bit amazed, as there are officials who simply can’t be bothered. People who always see a good reason why something isn’t possible but don’t offer any constructive suggestions either. I can get a bit “sour” with them. At the end of the day, they’re getting paid for their work.

What are you like, when you’re “sour?”

I say what I think, relatively directly, and that their approach just isn’t possible. I stay polite, but I don’t hold back. I don’t mind a situation escalating. If individual employees or bodies systematically block an issue, then you simply must bring it before the Federal Council.

But willingness to compromise is always a sticking point in politics. How willing to compromise are you?

I’m absolutely not the kind of person who feels the need to push through which direction Switzerland is heading in. I’ve always believed that an advantage of our system is that parliament, or, above all, the public, can decide. After all, they’re the ones who have to bear the consequences. In that sense, everything is always possible.

When was the last time you were truly surprised by a decision taken by the public?

The minaret vote (2009). I was sure it would be rejected. But it was accepted.

But direct democracy is a surprise package. Right up until the result of the vote, it’s never clear how it will turn out.

Yes, that’s true. But most of all, I think it’s a system that’s tailor-made for us, which also distinguishes us from other countries: we argue about politics, while others argue about politicians. We do it every three months, and they do it every three years. That’s a fundamental difference.

Arguing about substantive issues means I can say: I don’t agree with this! It might be different next time around. That way, you have a completely different relationship with each other.

Incidentally, the public haven’t always had as much of a say. That didn’t come in until 1874. The desire for a power of popular initiative came from the minority, not the majority. The minority thought there should be a power of popular initiative. That contributed to the way we can constantly question everything. And that’s a good thing.

“I find it problematic if 25% of the population decide which direction our country is headed in.”

“I find it problematic if 25% of the population decide which direction our country is headed in.”

And what about voter participation, which is often very low – doesn’t that equate to a lack of interest?

That’s disappointing. It isn’t always the same people who don’t vote. And if it’s something that’s really relevant to all of us, people do go to the polls.

There’s another way of looking at it: we’re happy that the votes aren’t always hauling people off the sofa.

But it’s true: I also find it problematic if just 25% of the population decide which direction our country is headed in.

Isn’t the biggest risk of our system, in any case, that the person who shouts the loudest can really undecided voters around them?

That’s actually something that gives me pause for thought. Along with the decline in the diversity of the media. That there are loud people who spread palatable, simple truths. When you look closer, these recipes are neither particularly palatable, nor particularly simple, nor particularly true.

But deliberately clear and simple.

Deliberately simple. But that’s something you sometimes forget when you study models of direct democracy elsewhere: It actually only works if you also ensure that there is a broad range of opinions and a high level of education in the country, so that everyone can tell to some extent whether a politician is talking “rubbish”.

“There’s nothing more irritating than people who think they need to be serious to be taken seriously.”

This interview will be published on August 1, the Swiss National Day. Last year, you gave a speech on the historic Rütli meadow. This year, you will be speaking in Diepoldsau in St. Gallen. What will you talk about?

August 1 is an opportunity to work out where we stand. This time, I’m going to talk a bit about the meaning of humor.

Why does humor matter to you so much?

It’s important in the life we live together, and in democracy, too. This is because humor creates a certain distance from others and also from yourself. People with a sense of humor don’t take themselves so seriously.

There’s nothing more irritating than people who go creeping along the walls with mopey faces the whole year round and stake a claim for feeling miserable. Those who believe they always have to be serious in order to be taken seriously.

Do you think you will reach a humorless person with a speech like that?

If they don’t get it, then that’s proof they don’t have a sense of humor (laughing).

There’s a really good book by Amos Oz – he’s an Israeli author: “How to Cure a Fanatic”. Amos Oz met plenty of fanatics. And he said the one thing fanatics have in common is that none of them have a sense of humor. Humor means being able to laugh at yourself and question yourself, to tell yourself that you might not always be right.

“I’m impressed by people who keep their sense of humor in the face of adversity.”

“I’m impressed by people who keep their sense of humor in the face of adversity.”

What kind of role does humor play in your personal life?

I would say a big role. I love to laugh.

Sometimes humor is a strength you develop in the face of difficult circumstances. I’m impressed by people who work like that. People who have the strength to get themselves or others back on their feet in the face of adversity. And to laugh even when they might feel like crying.

I’m convinced that a certain gravity is required in order to have a sense of humor. It’s also something I really appreciate in other people: I’m drawn to people who make you laugh, who convey a certain cheerfulness, an optimistic mood, people with drive.

What don’t people know about you?

That I have a lifelong love of walking and skiing – occasionally on my own.

Is that how you find a balance for your busy day-to-day in the Federal Palace? Are there sometimes periods where you just can’t stand to have anyone around you?

Oh yeah! Sometimes, in the Federal Palace, it can get crazy.

Although I have an open-door policy, the moment you think, right, now you’ve got a minute to yourself, someone is always coming in. After two or three days, I’ll have had enough. That’s when I either go jogging or close my door. And then I just sit down and stare at the ceiling.

Or I finish off writing things in peace and quiet. In any case, I’m usually working on some kind of text or speech or paper I should finish. But I need to be able to concentrate to do that. If people are always coming into my office, it eventually just becomes too much.

I’m not much use after the weekly Federal Council session on Wednesday afternoons, either. Preparations begin over the weekend. On Monday and Tuesday, the stress ramps up. On Tuesday, it goes late into the evening. Things ease off on Wednesday, after the Federal Council session.

Afterwards, I try to make sure I do something completely different.

“If I had a lot of time, I’d probably be grumbling that nobody needed me anymore.”

“If I had a lot of time, I’d probably be grumbling that nobody needed me anymore.”

You’re 55. The last ten years of your working life are ahead of you. You say you like to drift through life and don’t like to plan things. But is there anything you’d like to have more time for?

Yes, I love to read. I definitely don’t get round to it enough.

Are we talking about math books again?

That’s just an example. I like political biographies, too. And sometimes I’d like to do more sport, and have more time for family and friends.

How would you fill the free time with family and friends?

With travel, brunch, movies. You often have to give up things like that in this role. You either don’t have the time, or if you do have the time, you’re just glad to be able to spend time at home in peace and quiet.

The dilemma would be easier if I just had some tiny gaps in my schedule. On the other hand: If I had them, I’d probably be grumbling that nobody needed me any more (laughing).

Writer: Anna Maier

Images: Anna Maier

After a four-hour walk, Anna Maier and Walter Thurnherr reach their destination in Habkern (canton of Berne).

Newsletter

Subscribe to our newsletter and you'll get notified every time a new article is online.