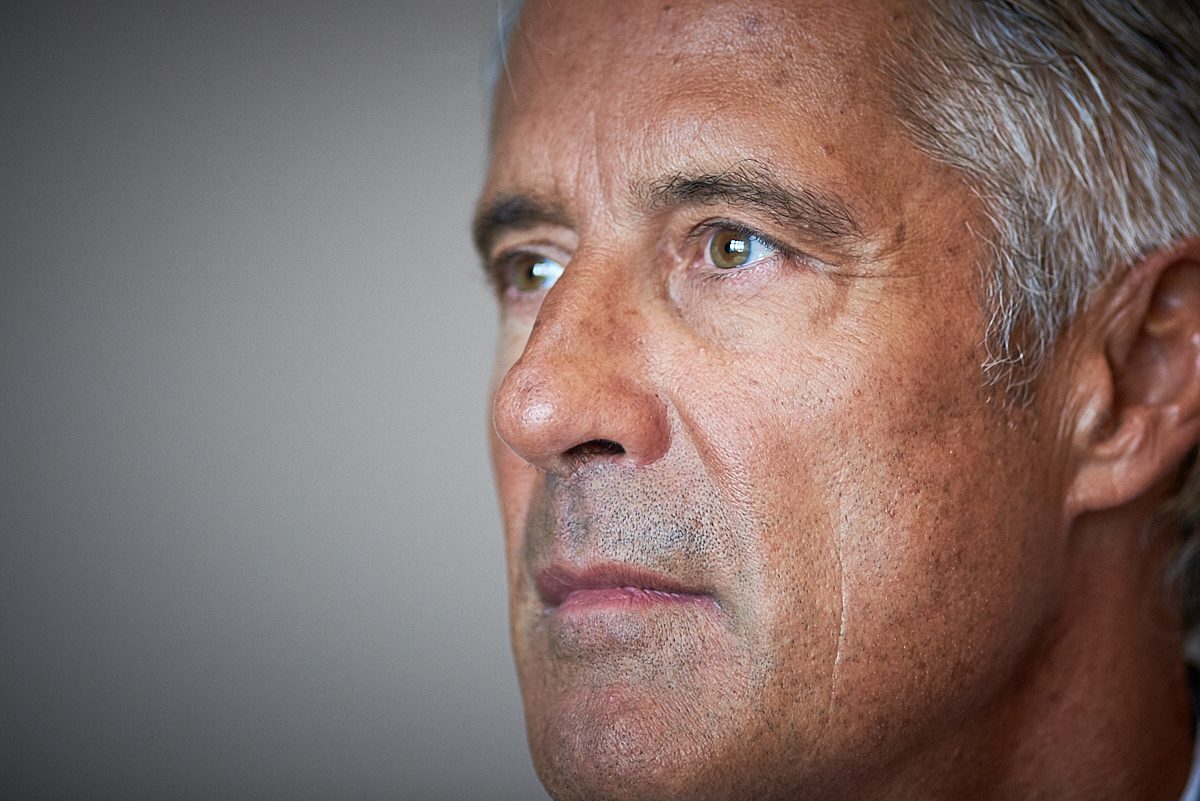

“People boo and whistle at the opera, just like on the soccer field.” Andreas Homoki, 58, artistic director

Andreas Homoki, curly-haired and perennially clad casually in jeans, is an artist through and through, modern and wild in his ideas. Even if he sometimes ruffles feathers, or hears the odd boo now and then.

Anna Maier and Andreas Homoki in the Zurich Opera House’s Spiegelsaal

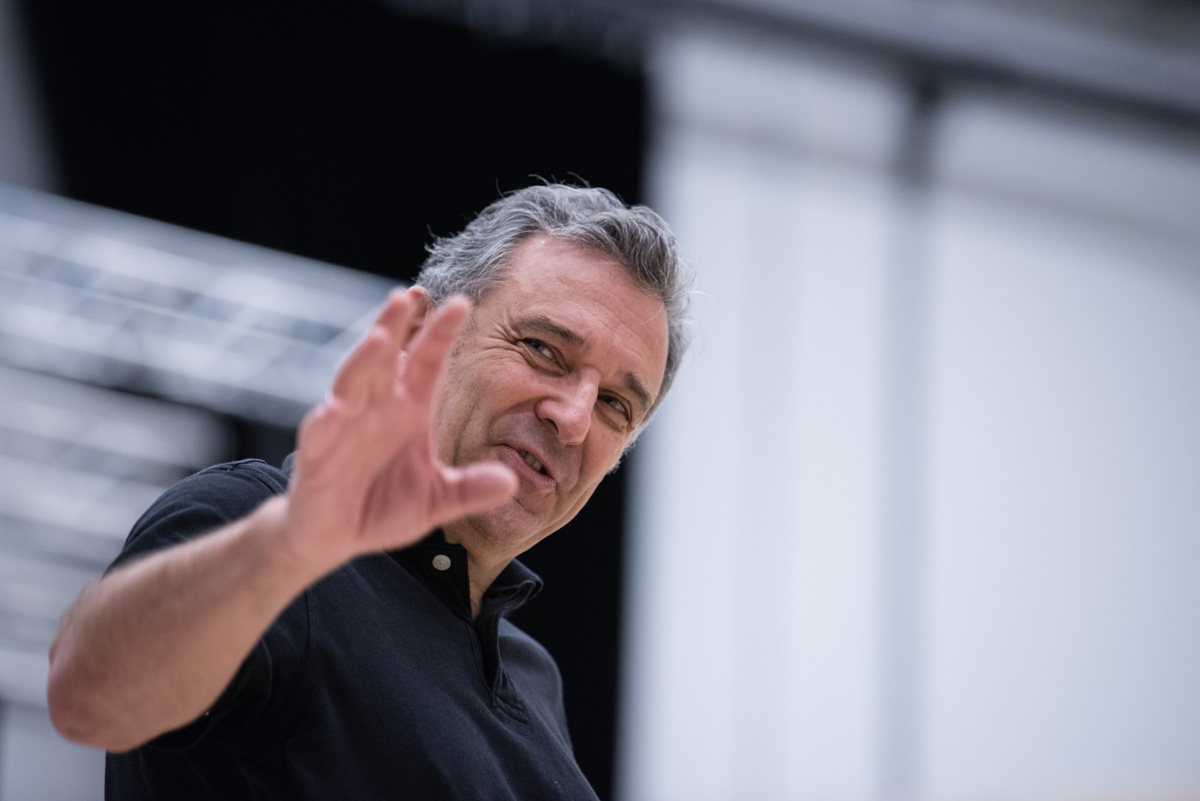

Andreas Homoki has a charming way about him: carefully listening to questions, engaging in the conversation, staying open, and refusing to take any prisoners. It is clear that he is creating a different culture from that of his predecessor, Alexander Pereira.

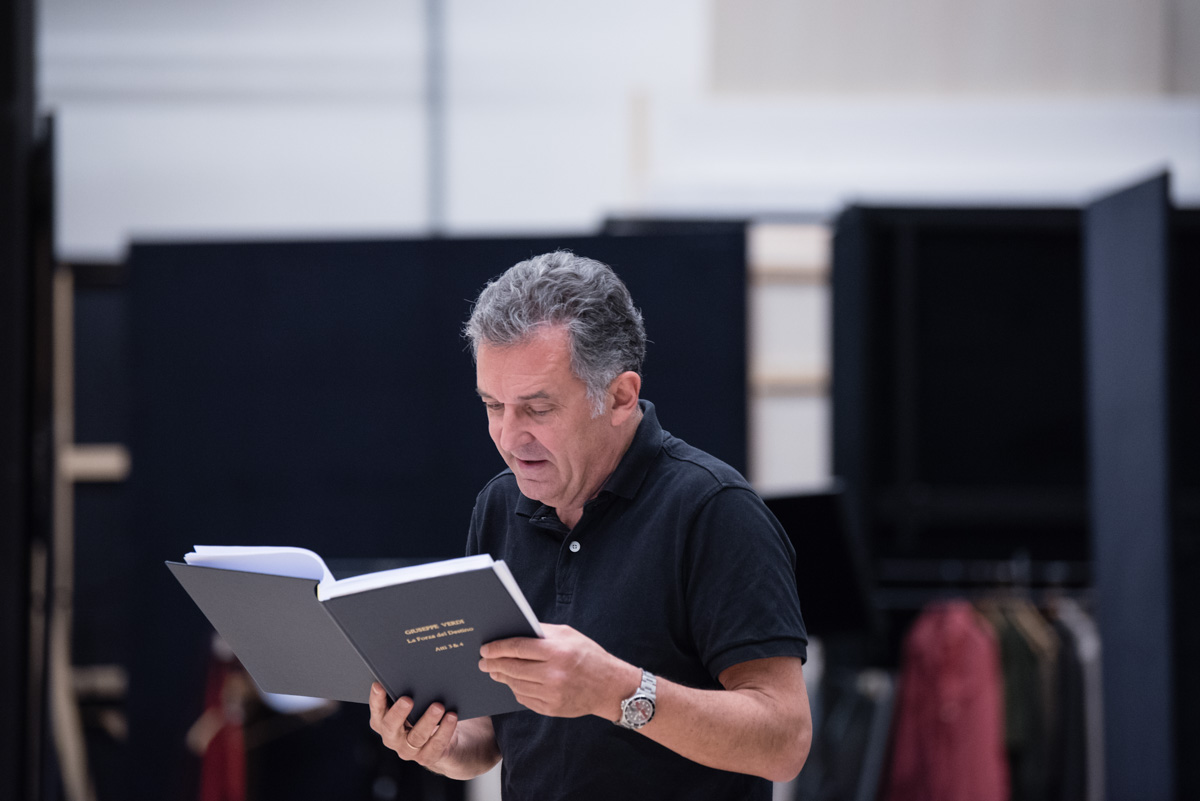

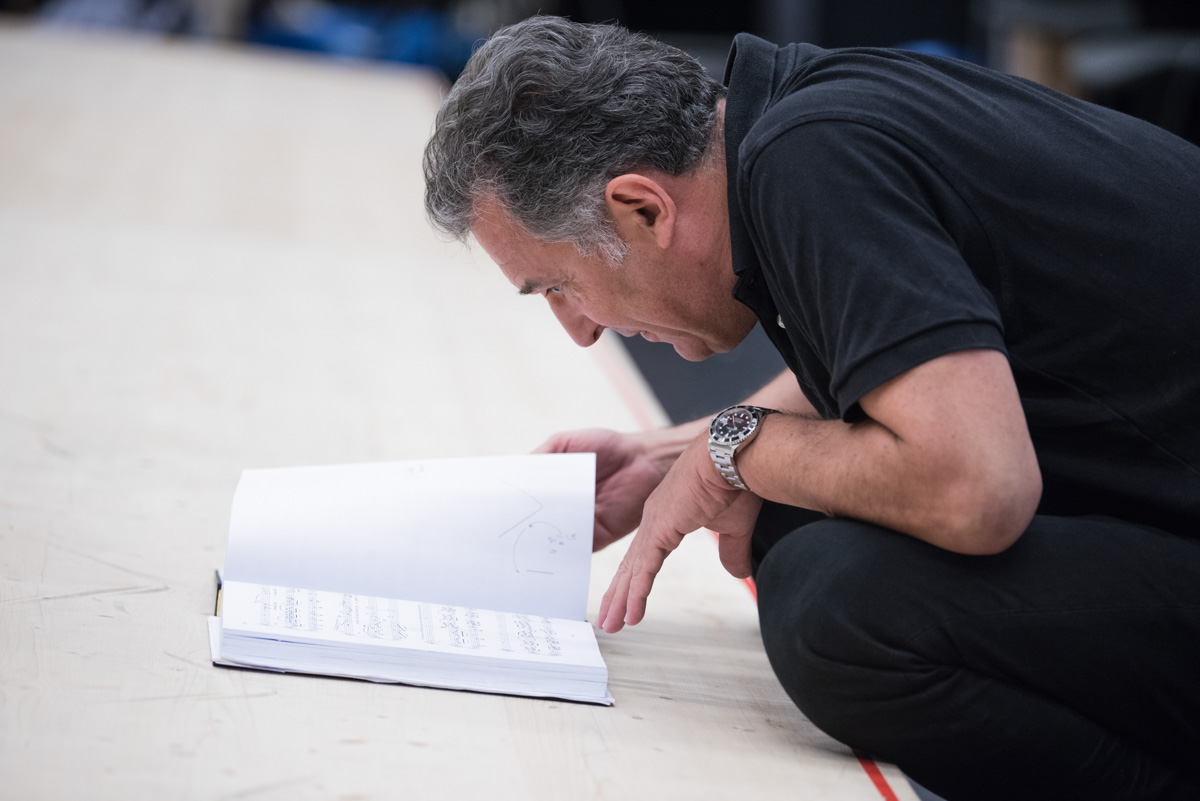

While Pereira spent 21 years in lofty circles, celebrating the glamor and glory of the Zurich Opera House, director and trained musician Homoki is more likely to be found at rehearsals and among artists than in the director’s box.

The native German with Hungarian roots, who turned the Komische Oper Berlin into the Opera House of the Year as its artistic director, is fighting on the artistic front to combat a general downturn in audiences. And succeeding. Even if he hears the odd boo now and again. As was the case just recently, at the premiere of “La forza del destino.”

We talk about the grander and smaller dramas of the world of opera, and why he has no scruples about making unpopular decisions or leaving a boring performance now and then.

“I’m not a control freak!”

“I’m not a control freak!”

Anna Maier: It’s not easy to peel you away from your work and grab you for an hour-long interview. How do you make sure that your passion for the opera doesn’t consume you entirely?

Andreas Homoki: I rarely get stressed. A good artistic director knows how to delegate. I have handed over many decisions on day-to-day operations to my team. We have nine, ten new productions every season and 18 revivals in opera alone, so you can’t do everything yourself – and nor should you.

My core skill is creative work as a director. It shapes my view of the opera. This is the question that matters to me most: who is the right person for a production?

Can you, as a known perfectionist and an artist yourself, who presumably likes to keep an eye on everything, truly give up control?

I’m not a control freak. But there are clear guidelines for what matters to me. Within these standards, my staff can and should make decisions of their own accord. For example, in casting all the different operas we put on, of which there are around 28. If I wanted to monitor them all, that would slow down the process way too much.

But my teams know exactly when it’s better for them to ask me to make sure something suits me. That means you have to work closely together.

So, for example, my opera director and I sit in on the final rehearsals for every single production together. We already know what the other person likes and what they don’t like or what annoys them.

Do you sit in on rehearsals so you can have your evenings to yourself?

No, I do it because quality control happens in the rehearsals. I don’t have to go to every performance to know that it’s going well. It’s much more important to make sure that the right processes are in place for a convincing and solid performance. If can spend an evening with my family now and then, then that’s a bonus, of course.

“Of course I understand that people like to see the director in his box.”

“Of course I understand that people like to see the director in his box.”

Your predecessor, Alexander Pereira, is thought to have spent more time at performances than you do. This has been the subject of criticism, especially at the start of your tenure at the Zurich Opera House. How often do you actually watch the performances from the director’s box?

Of course, I understand that people like it when they see the director in his box. But most of my work is done before the audience sees a piece or me sitting in the director’s box.

Before a piece is premiered, I have already seen the production several times at various rehearsals. After the premiere, I attend a few more performances.

Around half of all the 180 performances we stage in the opera alone are new productions. The other 90 are made up of 18 revisions of existing productions. I always see at least one of them. That’s important, because, of course, the artists involved want the artistic director to notice them.

How do you tell that someone is extraordinary?

You can tell when you forget the performer as a person and their own individual effort. I call that transformation. Everything goes into the overall experience and you experience the story with tremendous emotion.

This is precisely what it is about! Unfortunately, that happens all too rarely – because the conditions in rehearsal aren’t right, for instance.

“There is something ecstatic about the opera.”

“There is something ecstatic about the opera.”

When you were five years old, you saw “Carmen” in Bremen. Your father was playing in the orchestra as a clarinetist. Was that where your fascination with opera was born? What happened then?

Yes, I loved the music first and foremost. The impact of the orchestra and the choir, the emotional power when they let rip together. I thought that was special. There was something ecstatic about it. But I didn’t really understand the story back then.

Later, I liked the opera less, since – as I see it from today’s perspective – it was presented in a way that was just completely inadequate, badly produced – unconvincing, boring.

Banal? It’s said that you hate banality.

Yes, if it rings hollow. Banal can also be funny, if it’s deliberately so. You can enjoy banality too, but it has to be in the right context. When I was a teenager, I actually loved the movies. I still do.

“I can quickly tell whether someone is capable of moving me.”

Can you tell from looking at someone whether they have the talent to stand on stage and move people emotionally?

I can’t tell from looking at them, but I can quickly tell whether someone is capable of moving me. If something happens with a character.

As a director, when you work with an artist for the first time, you are faced first of all with a stranger. And, hopefully, a mutual interest in creating something beautiful.

The exchange has to be trusting, so that the performer feels that I don’t just want to criticize them, but that I want them to be good for both our sakes.

Although, since I’ve been in the business for a long time, I can tell immediately whether someone is a professional or whether we’re on the same wavelength. But then at some point there has to be the crucial moment where you can sense that this person is transforming and standing out from the rest.

That’s what it’s about! That’s what has to happen on stage.

Of course, this transformation has a bigger impact, the more people it affects. When it’s an ensemble of three or four people, perhaps with a choir, and all of them rise up into this whole, that can be tremendously moving. You are witnessing the creation of a collective – together with the audience.

When it comes across to the audience as inauthentic, there can be rejection, too. Then the heightened emotions lead to booing and whistling, like on the soccer field.

“Booing is something you have to live with.”

“Booing is something you have to live with.”

You were booed yourself by the audience for your production of Giuseppe Verdi’s “La forza del destino.” With good reason?

Booing is often part and parcel of an innovative production. Particularly for productions that collide with traditional views. You have to live with it.

How hard does this kind of rejection from the audience hit you, especially given that you and everyone involved have put your heart and soul into the production?

It doesn’t really hit you. In actual fact, there’s usually a huge controversy within the audience itself. With some booing, and others replying with bravos. There are even said to be directors who hire extra people to boo to provoke lots of bravos.

What is it about this particular piece that cursed it?

The piece is very demanding for all involved. The vocal parts are just extraordinarily difficult. That leads to nerves, singers get sick, might drop out. There are some script-related snags, too. All of that makes the production process very fragile.

“If I get bored, I leave in the interval.”

“If I get bored, I leave in the interval.”

Drama at the opera. What happens to make you, as an audience member, leave a performance?

If I feel like I’m not being taken seriously. But, of course, I don’t leave while the performance is happening on stage. If I get bored, I leave in the interval. Life’s too short. It was even in the newspaper.

The fact that last year, you attended the premiere of The Threepenny Opera at the Zurich Schauspielhaus and left. In the newspaper, there was criticism that you left as the artistic director of the Opera House and not as Andreas Homoki.

Being an artistic director has its limits, though. Sometimes, I’m just Andreas Homoki.

Sometimes, the line between career and calling can become blurred. Can you draw a clear line between them?

Yes, and I do. When you represent such an important institution, of course, you’re in the spotlight. You have a responsibility, not just for 600 employees, but also for the widespread acceptance of this art form, which costs a lot of money. The canton gives us eighty million Swiss francs in subsidies every year.

And that’s still not enough…!

And that’s still not enough. And you have to earn more on top of that, as the Opera House generates 37% of its budget itself. Given the large subsidy from the canton, I can understand that as an art director, you are under special scrutiny.

“It would be fatal if I didn’t appear authentic.”

“It would be fatal if I didn’t appear authentic.”

You wear two hats. On the one hand, you’re an artist, but on the other, you have to make sure that subsidies and sponsorship money are coming in. How do you manage to succeed in these two extremely different worlds?

I just always try to communicate my intention. Like at a rehearsal, where I encounter an ensemble for the first time in a theater where I’m a total stranger. I tell them what I want and try to get the people on board and inspire them.

With sponsors, it’s actually very similar. Sponsors are people who support culture and love culture. They really appreciate it when they can sense who I really am. It would be fatal if I didn’t appear authentic.

And in any case, there aren’t many industries as varied as the world of opera: on the one hand, you have the artists, who appear emotional, and on the other hand, you have the sponsors, who often come from the rational world of finance. They’re politicians or businesspeople, who move in completely different circles. What are the common denominators?

When you meet a leader, irrespective of the industry they’re in, they always have a strong personality. They are people who deal with problems and understand the big picture.

Someone who can’t see past their own nose will never become a great artist or a leader.

“I’m not part of a work of art, thank God.”

“I’m not part of a work of art, thank God.”

To what extent are you a man of contradictions?

What do you mean by that?

For example, you often say that the opera is brought to life by costumes. But at the same time, you go around in your own uniform, wearing the same brand of jeans and the same jacket for years, because that’s what you feel comfortable in. They’re different things.

I don’t have to go on stage. I don’t have to transform into a character.

Artistic directors are always trying to land a coup and engage a prominent fashion designer for the outfits. That usually goes wrong, since a costume designer isn’t supposed to design beautiful clothes. They’re supposed to create characters. You use costumes to create a world.

When a character comes on stage, I need to know immediately who they are, what their character is, how they act towards others. It’s a very artificial entity.

I’m not part of a work of art myself, thank God. I dress in clothes that make me feel comfortable and in a way that I think I look good.

When did you actually first decide: “These are the jeans that suit me, I’ll wear these forever”?

Well, I’m really lazy when I go shopping. I changed my brand of jeans two years ago, by the way.

All done with the 501s?

Yep, 511s. They’re slimmer. I bought them once by accident. Then my wife said: “You know, they actually look better.”

“Cinema intermissions are a real plague, pure commerce.”

“Cinema intermissions are a real plague, pure commerce.”

Another contradiction: you love going to the movies, but you hate the intermissions. And yet in the opera – when you’re right in the middle – there’s a break.

In the opera, the pieces are often designed that way. After the first act of Lohengrin, there has to be an intermission, there’s a huge build-up with a massive pay-off. You can’t go straight ahead with that.

Do you really think that, or is it like in the movie theater, where you can sell expensive drinks and snacks during the intermission too?

When you perform a shorter piece without an intermission, of course you lose the money from refreshment sales during that break, but an artistic decision has to take precedence.

On the other hand, movie intermissions in Switzerland are a real plague – pure commerce, with sentences being interrupted halfway through. Now there’s even advertising in the middle. Unbearable! That’s why I practically only ever go to the Kosmos movie theater in Zurich now. There are no intermissions there.

Do you personally feel that the opera needs this moment of taking viewers out of the action?

It depends on the piece. You wouldn’t want to see Ben-Hur in the cinema without an intermission either.

Are there pieces where you say, this will only have intermission over my dead body?

Yes, I did Fidelio without an intermission. But we took all the dialog out of it, so with the music, it was just 1 hour 50 minutes – perfect. I’ve put on a few Puccini operas that way, too – Manon Lescaut, Boheme and even Turandot.

“Here, no one needs to sing a role that doesn’t suit them.”

“Here, no one needs to sing a role that doesn’t suit them.”

I recently interviewed a tenor who was with the Bavarian State Opera. He told me how he experienced burnout at the peak of his career, because he didn’t draw a line between his career and his calling. Can you tell when someone in your ensemble is reaching breaking point?

When a singer is tired, we hear it in their voice. So we take great care to ensure that our artists have the opportunity to recharge. Here, there isn’t the same pressure as in smaller theaters, where soloists have to sing almost every night because there’s a shortage of personnel.

We also cast very specifically to someone’s skill set. Here, no one needs to sing a role that doesn’t really suit them, which sometimes also happens for financial reasons.

“Sometimes my son complains and says: ‘Why do you do that?’”

People credit you with modernizing the Zurich Opera House. You are bringing new, younger people into the opera. Yet one of the major issues is surely that the older, loyal clientèle is getting smaller. How do you get young people excited about the opera? Like your son, who is 20 years old and a real movie buff. Do you bring him to the opera?

He actually comes to the opera a lot, and it really interests him – particularly the staging. When he notices that a performance is mainly a vehicle for a certain singer and the staging is bad, he complains and says: “Why do you do that?”

He takes the art form seriously and has a good eye, too. He got this from his mother and me. She is a singer and he saw her on the stage from a very young age.

It’s true that we generally have to widen our pool of potential opera-goers. Regular attendees also used to come to the opera more often. Today, there are more members of our audience who come now and then, choosing from a very wide range of cultural offerings.

So why should people go to the opera?

Because it’s somewhere that offers a totally unique, emotional experience. No other medium can actually do that. Theater can’t, because it doesn’t have this musical emotion, the expansion of the story into this whole other scale, and movies can’t, because they don’t have that directness, you can sense the content has been pre-produced.

The fascination of something happening in this very moment, through a vocal performance that isn’t just brilliant, but is enmeshed in the fabric of this artist in this particular role – that is something very special, and you can only find that here.

Unfortunately, it’s a tremendous luxury, because it needs a lot of staff. There are 600 people. 450 full-time staff.

“Unfortunately, the opera is a tremendous luxury, because it needs a lot of staff.”

“Unfortunately, the opera is a tremendous luxury, because it needs a lot of staff.”

80 million in subsidies, 9 million in sponsorship. You even make a profit. Why does it take so much money to keep it up and running?

Of course, you don’t need that much money for every form of musical theater. What sets our theater apart is that we offer 180 opera performances per season, with lots of variety – 28 different titles, of which nine are brand new productions. There are also 50 ballet performances and three new productions.

There are opera houses with only 60 performances a year or just five titles – like in the US or France and Italy, with far fewer technical staff members and without their own orchestra and choir. But there are also opera houses with even more performances and more titles – like in Vienna.

The question is, what kind of musical theater do I envision? How much does the precision of the production matter to me? This needs more time, which reduces the range of what we can offer.

I often pose the rhetorical question: How would you have to run an opera house to make it commercially profitable? You would have to bring out fewer new productions, first of all. In extreme cases, you’d play the same one every night. Then reduce the ongoing performance costs. No more sixty-person choirs and sixty-person orchestras, but fewer musicians and the smallest cast of performers possible. Like on Broadway in New York or in London’s West End.

“The alternative would be the eradication of opera.”

“The alternative would be the eradication of opera.”

Things seem to be working out nicely in those cities.

Yes, it works, and that’s where a tremendous amount of theaters are based. They play the same piece every evening.

Then, a year later, they come back and play the same thing again. That doesn’t work here. Here, we put on a total of 230 performances a year, opera and ballet combined, in front of 1,100 people, every night. With “Cats,” I’d be done after a month and people would no longer attend. Something like that only works with hundreds of thousands of tourists. We make theater for a city and a region, so you have to guarantee variety.

Human labor is simply very expensive nowadays. So musical theater is an art form that from a cost perspective is wholly behind the times. You need the political will for this to happen. The alternative would be the eradication of opera as a living art form. Then it would only exist as a score or a CD.

You mention timeliness. Shouldn’t the opera draw more on current issues, so that young people aren’t just attracted by the music, but also because something is happening on stage that’s relevant to them?

Everyday life is difficult to depict in an art form that is ultimately designed for longevity. Of course, there are also contemporary opera productions, but opera is about telling stories that are timeless and present the certain basic patterns of our lives in different ways.

“The opera shouldn’t degenerate into a museum.”

“The opera shouldn’t degenerate into a museum.”

The operas that are part of our canon today are actually only a small selection of the pieces that have been written, namely those which have survived. Why have they survived? Obviously because they were extraordinary successes, but also because they involve issues that still affect us today. There are also operas that were very successful 150 years ago and are no longer of interest to anyone.

The important thing is to interpret the pieces in such a way that their timeless quality becomes apparent. Otherwise, the opera degenerates into a museum and a young person who goes to the opera rightly says: “Are you kidding? Why should I watch this?” Those of us who create opera have a duty always to come at the pieces from new and critical perspectives, even if this upsets certain opera-goers, who would like everything to stay the way it used to be.

“Then this terrible thing happened. He suddenly had to appear before a court.”

The controversial Russian director Kirill Serebrennikov was set to make his debut here at the Zurich Opera House on November 4. However, he is currently under house arrest in Moscow. How are you handling this situation?

I met Kirill a year and a half ago in Berlin, at the Komische Oper. We got talking, I looked at some of his stuff; then he came to Zurich, took a look at our place, and we finally agreed on Mozart’s “Così fan tutte.”

And then this terrible thing happened. He suddenly had to appear before a court and was placed under house arrest.

It’s a terrible situation for him first of all, but it’s also a problem for us. At the end of the day, we have to have something to show on stage on November 4. But we also want to hold out for him as long as possible.

We set ourselves a deadline: If nothing changed by mid-February 2018 and it didn’t appear likely that he was coming out, then we would trigger a plan B where we went back to an existing production.

Then this deadline arrived and I had to make a decision, but I couldn’t.

“If all else fails, I’m here, too.”

“If all else fails, I’m here, too.”

So he wasn’t replaced. Is there no plan B?

I talked to my family about it, too, and both my son and my wife said that I couldn’t do it. So I spoke to my team again and we all agreed: we’ll go ahead with it whatever happens!

The set design has already been created in collaboration with a set designer colleague of Kirill Serebrennikov’s. They will also be here with us.

Then there is a choreographer and a video director with whom Serebrennikov works regularly. They have been familiarized with the concept and are already involved – they will develop the piece with the singers if need be.

Of course, it will be different than if he were here himself, but “Così fan tutte” will go ahead on our stage on November 4. This way, I have upheld my duty to the audience.

If all else fails, I’m still here, too. I’ll be here the whole time.

Are you handling the piece yourself?

I assured Kirill that I would watch the rehearsals and help the boys if there were any problems. So I am there as an “added back-up,” so to speak.

“I have a clear picture of what a totalitarian society is.”

“I have a clear picture of what a totalitarian society is.”

Some say that Kirill Serebrennikov misused public funds. Others say that he is being made an example of, because of his criticism of the government. How do you view the situation?

I think it’s the latter.

What can you do for him?

Not much, I don’t think. Today, over 25 years after the fall of communism, Russian society and Russian institutions have apparently resigned themselves to living in a much more authoritarian structure than we in the West would have imagined and hoped after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

From the outside, you can’t do much. That just leads to the usual political defense mechanisms.

Your parents are from Hungary and moved to Germany, where you grew up. What have you picked up from your family history? What did you learn from your parents?

Well, I have a clear picture of what a totalitarian society is.

We regularly went to Hungary and, of course, I picked up a lot. Including how flimsy the surface of the socialist establishment ultimately was, and how reactionary parts of society have remained, when it comes to resentment of minorities, anti-Semitism, etc.

That carried on underneath the surface, was never properly discussed and dealt with, and is only just surfacing now. We can see that in the wholly populist tendencies in the countries of the former Eastern bloc.

Do you still go to Hungary regularly?

My father died three years ago. Since then, my connection to Hungary has been very loose.

“I said I would do it for ten years. But I’ll stay longer.”

“I said I would do it for ten years. But I’ll stay longer.”

You are now 58. In two years, you’ll be 60.

60, that’s the age of grandpas.

Your contract with the Zurich Opera House would have been expiring two years later. We learned that you are going to stay until 2025. What would you like to achieve in the following years?

I don’t feel like there are fundamental things I’ve missed out on. At the moment, I really enjoy being able to practice my profession here in Zurich at an unparalleled level in terms of quality. I also have an artistic and financial freedom that I wouldn’t have in any other opera house in the world. Here, I’ve found my ideal overlap between the two.

Although you have acquired a couple of gray hairs during your time here…

But I’m doing very well on that front for 58! Some people already have white hair at 45. Or have no hair left on their heads at all (laughing)

Andreas Homoki in conversation with Anna Maier

Interview: Anna Maier

Images: Claudia Herzog

Newsletter

Subscribe to our newsletter and you'll get notified every time a new article is online.