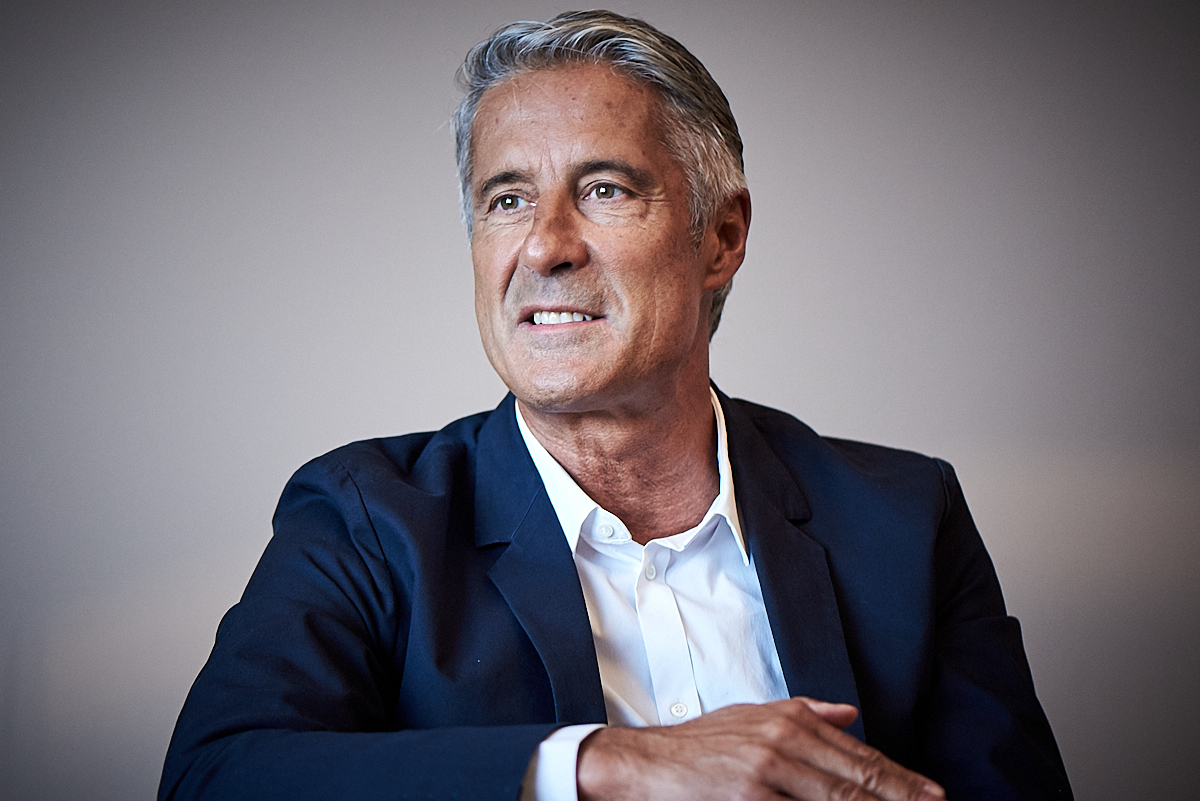

“When you’ve seen a massacre, you can’t carry on living life as normal.” Enrique Steiger, cosmetic and war surgeon

Enrique Steiger is a cosmetic and war surgeon. They sound like two parallel universes, but they actually create a useful symbiosis. His network is helping him create a humanitarian hub for war zones.

While the good things in life await him at home in Switzerland, in war zones, he’s faced with misery and suffering and images he can’t easily shake off. Yes, the headlines write themselves. But it doesn’t do justice to this Richard Gere lookalike to plaster a brief “From Botox to bombs” headline over his handsome face.

Someone who puts his life on the line because he’s needed where few dare to tread, who looks on while patients and colleagues are slaughtered, shouldn’t just be reduced to the supposed paradox that he also makes the world’s rich more beautiful.

I was less interested in this part of his resume. Instead, I wanted to understand how the boy from Witikon in Zurich, half-Swiss, half-Argentinian, became one of the world’s top surgeons. Someone who doesn’t sit back feeling satisfied by his successful career, but someone who has battled for years to make the world a better place in those places where it’s falling apart.

“Even after all these years, I still feel a sense of awe at every incision.”

Anna Maier: In every career, there’s an early experience that evokes pride. For instance, when an architect stands outside a house they’ve built, or a singer hears their song on the radio for the first time. Did you also have an early experience like this where you thought: I can pat myself on the back for that?

Enrique Steiger: An early experience that has always influenced me a little as a surgeon is when I came to Uster (in the canton of Zurich) as a fresh young assistant and had to operate on an appendix on my own on my very second day. That morning was when I first saw how it worked.

I called my boss and said: “Professor, it’s an appendix.” I thought he’d come, but he just said: “Yes, do it. See one, do one, teach one.” That was his answer.

So on my first day, I operated on my first appendix. The appendix isn’t for beginners. I gave myself a good talking-to. You know the whole anatomy properly. You know where you need to find it. You know the danger zones. If you avoid them, nothing can go wrong.

Luckily, I had a great theater nurse. To cut a long story short: the nurse led me through the operation so well, she practically did it for me, but she never gave me the impression that I wasn’t up to it myself. I went to bed and probably said three Hail Marys that the patient would live.

On the next day, my boss came and the patient said he was doing really well, he wasn’t in any pain and wanted to go home. My boss looked at me and said: “See, just have a bit of faith in yourself and it’ll all be fine.” I just thought: He’s talking nonsense. What a risk he took. He, in turn, thought that I wouldn’t do anything I couldn’t, and if I couldn’t get any further, I’d surely call him.

At that moment, I realized that in our line of work, you have to be able to jump in at the deep end. That doesn’t mean putting patients at risk, but as a surgeon, you need a certain daredevil approach. Later on, you’ll often do operations that you’ve never seen before. At the end of the day, you always find a solution. That’s the only way you grow.

I think that was the spark I needed: this man had faith in me. So I thought: if I have faith in myself, too, it’ll all turn out alright.

But in the worst case scenario, the patient could have died?

That might be a bit too far-fetched, but he could have had a hole in his bowel, which could have led to an abscess. Then we’d have had to operate again. If he’d been very weak, he could have died of sepsis. So, in principle: yes.

Today, there’s none of that any more. Those days are long gone. Today, people are totally risk-averse. That’s an aspect of our society that I doubt is good. My parents’ generation was much more courageous. You can tell they lived through the war. They needed a lot of courage. They did a lot of really crazy stuff. But that allowed them to change their lives more or less for the better. If they hadn’t had that courage, they would all have been as risk-averse as our politicians and leaders are today.

I can say: without that first jump into the deep end, I wouldn’t have come so far.

A surgeon once told me that probably no other surgeon would say it was true, but there’s something godlike about when you say “incision” in theater and everyone waits for you to make the incision and wound an intact human body. Do you get used to it?

I know what she meant by it: not that we’re godlike, far from it, but that we’re taking a crack at God’s masterpiece and wounding it ourselves. We’re manipulating a being that we uphold ourselves. You have no reservations slaughtering a calf, but with people, it’s completely different. With humans, there’s a sense of awe.

Even now – after all these years – I still feel a sense of awe at every incision. Because you know that you’re millions of miles away from the perfection of human beings and their reproduction. When it comes to reconstruction, I’m far from godlike perfection. As a trauma surgeon, I was far from understanding exactly how balanced the human machine is.

One reason I didn’t go into neurosurgery was the respect I had for how demanding the operations were. Even today, when it comes to neurosurgery, we’re only scratching the surface. Although we claim we’re going deeper, we’re still miles away from the actual possibilities of neurosurgery.

That’s why I told myself, I’m going to stick to the surface. But back then, I underestimated how challenging that surface can be.

What do you mean by the surface?

Down to the muscle. To me, “deep” means the digestive system, the heart, the lungs, the brain and so on. We’re often called “surface surgeons” a little disparagingly, because we work with the bones, the skin and the soft tissue. Yet there are very few surgeons who know this “surface anatomy” in as much detail as plastic surgeons.

“I’ve got no time for feelings when on a mission.”

You started out in trauma surgery. What did you work on? What kind of patients did you have on the table?

Mostly patients with multiple injuries, suffering from severe trauma, who had fallen from a crane, for instance, got into serious traffic accidents, or suffered burns.

Back then you were still very young – just starting out. Isn’t this a very demanding field for your first steps as a surgeon?

Let’s go back to my first operation: I have always sought out challenges in my life. No matter what I do, it has to be demanding. I always found that internal medicine, with its complexity, or dermatology, or oncology, which is extremely demanding, are all absolutely fascinating, but the surgeon is the doctor who can solve almost any problem.

A surgeon can also treat internal conditions – if they’re interested in doing so – while a specialist in internal medicine can’t perform heart surgery. They can’t do it. That’s why I’ve always thought the doctor equipped with the most tools is the surgeon.

I then experienced it later on, too: as a surgeon, I could solve every problem. I could even misuse my anesthetist as an internist. I told him he needed to look after these things. He had to work out how much potassium this person needs. As a surgeon, you’re the doctor across the board.

When we talk about accident victims who come to you maimed and torn: how do you manage to avoid this sight affecting you the way it would affect me?

There’s a big difference between how you and I look at the person who’s injured. You see them as a person who’s suffering. I don’t bring any emotions into it. Of course I have empathy, of course I’m sorry for the person, of course I want to help them, but I don’t feel any emotions for them.

I look at them from a technical perspective. I almost break them down into their different parts. I scan them from head to toe. Are they conscious, are they breathing, is blood being supplied to their vital organs? A network of blood vessels, nerves, bones and so on is mapped out in front of me. A scan develops in my mind, a kind of three‐dimensional representation of the injury.

Then I go deeper and try to find out where the bullet went in, which organs have been damaged. That’s all happened before I’ve even sent them for an X-ray. I start with analysis and considerations. I have no time for emotions. The patient doesn’t want me to have emotions, either. They want to have their problem solved as quickly as possible. That’s my perspective.

How did you acquire it?

If you can’t do it, then you’ve got no business being in our line of work. If you get emotional – and I’ve never seen a surgeon who gets emotional – then you’re in the wrong job.

Yet there are military doctors who can’t really deal with the situation, aren’t there?

Yes. We once had a refugee camp in Goma. We set it up during the massacre in Rwanda in 1994. Six months later, after I came home, I was watching CNN and saw a report where one of my patients was being carried into an ambulance center on a stretcher.

A young French doctor was walking alongside him, holding his hand and crying. I thought to myself, if she had been in our team, I’d have sent her back home on the spot. For one simple reason: she had nothing to cry for. She had to show strength. She’s the only beacon for these people in their distress.

If I, the patient, see the doctor crying, then I get afraid that they don’t have the situation under control. You have to look at the situation completely coldly, analytically, not without empathy, but without emotion.

“You soon realize it’s not a game, it’s a bitter reality.”

When you were very young – still an assistant doctor, as far as I know – you went to Namibia with the UN, to the border with Angola. What happened to you there?

It was shortly before the war ended. The UN was there to ease the transition to peacetime. I was sent there as a young officer in the rank of first lieutenant of the Swiss Army to work as the chief doctor for the entire Sector 10 region. There were around 4,000 units stationed there to guard this border, from Indonesia, Finland, Malaysia, Italy and Spain. They had to make sure international agreements were being observed.

I was in my fifth year as an assistant doctor and had long wanted to do a lot more. I felt I was progressing too slowly. I wanted to take a sabbatical for five or six months and go sailing with friends in the Caribbean.

Then my current partner came to me suddenly and told me they were looking for UN officers to go to Namibia. I thought I could kill two birds with one stone: I’d have an Out of Africa-style adventure and earn my way up to a higher ranking in our military.

So you pictured it as a romantic adventure?

Yes, I wanted to work my way up on a romantic adventure. Ultimately, nothing came of either. When you land at a military base like that for the first time, where countless injured people are being brought out of carrier planes, fighter jets are being armed and starting by the dozen, you realize it isn’t a game any more. It’s a brutal reality.

The blessing in disguise for me was that every other unit in the country had peace. Only in my sector were there rebels who didn’t want to give up their arms and were liquidated or hunted by the South African army. We collected the patients in these missionary hospitals, brought them to our little hospital and put them under UN protection, which we actually really weren’t supposed to do. There, we had quite a lot of people with severe injuries, particularly gunshot wounds.

What do you mean, “we weren’t supposed to”? Did you take it upon yourselves to act?

Yes, we had no mandate to protect them.

Why did you do it?

I thought, that’s the right thing to do.

You don’t like following orders?

No, I’m happy to adapt to a system. But when I find that the system doesn’t work, then sometimes you just can’t get to me. Back then, we only had telex and radio…

What would have happened if you hadn’t looked after these patients?

They would have been captured, tortured and then probably disappeared.

Probably, or did you see it happen?

Yes. You have to know that they were still in war mode at the time. There were the Koevoets, a special South African unit, who were used to killing people on a large scale. That was their job. They had to destroy their opponent.

As ever, when a war comes to an end, there are a lot of people who can’t exist outside a war zone. They’re what are known as “war junkies”. They’re very dangerous. Even in an orderly, civilized country like South Africa, there were these elements who were still on the hunt, although it was proclaimed throughout the country that the fighting would stop.

But they thought that others had violated their laws and didn’t belong there. It took a few months for these people to adapt. We contributed a lot by saying point-blank: “No way! It stops here.”

Did it work?

Yes, it worked. The officers I worked with, the special services, the special units, always saw that we made a great effort. They saw that people accepted us very quickly.

Are your scrubs a sort of shield in these situations?

As a doctor, like a preacher, you’re often the most credible person, when you arrive as an outsider.

And the most helpful, right?

Yes, the most helpful and the most credible. You know our Hippocratic oath is like the clergy’s oath of secrecy. For doctors, it goes even deeper than that. I also speak six languages fluently. Although I couldn’t speak Afrikaans, everyone understood English.

I was young, naive, affable and optimistic. So were all of my colleagues. We got together and said it makes sense to protect these people. There wasn’t much discussion. Then there were journalists who heard about it and made it public. As there was positive feedback from the press, we got away with a slap on the wrist, although we were convinced we’d done the right thing.

At that time, Swiss people were completely inexperienced in overseas missions. Our leader himself didn’t know how a mission like that was supposed to run. What we did on our own initiative was certainly not part of the UN mandate. We even had an incident that made it to the cover of the Herald Tribune.

What was it?

That we were protecting rebels from the South African army in a small missionary hospital.

And it was true?

Yes, it was true. The missionaries wanted us to look after these injured rebels. We saw this as our job and weren’t aware that the UN didn’t have a mission to protect them. The South Africans were incensed and UN headquarters in New York weren’t too happy about it, either. But since the South Africans didn’t want to be viewed negatively, and we were transparent and cooperative, the whole thing wasn’t pursued any further.

But I have to emphasize that the South Africans always conducted themselves entirely correctly. I only found out later that the state authorities didn’t always stick to the rules of the game.

“My wife saved me from becoming a ‘war junkie’.”

That was your first mission. Five months of adventure, and you came home a hero.

No, more like a tired little Swiss soldier who’s just come back from a tough refresher course.

What kind of an overall impression did you get?

Quite simply: what I liked was working with so many different people from so many different cultures to do a job. The job of bringing peace to a country that had only known war for 20 years. The recognition and gratitude expressed by the population for the work we were doing was so great that it filled us all with a sense of satisfaction and emotion.

I was then offered a head doctor position in another conflict in Cambodia. If I hadn’t married my wife and become a husband shortly before that, I would probably have gone. I think my wife saved me from becoming a “war junkie” who goes from one conflict to another.

I get the impression that you are, though, otherwise you wouldn’t have gone from conflict to conflict for nearly 30 years and continued to operate there. What happened the first time that you wanted to experience again and again?

I realized I was born for this life. It matches my skill set.

A calling?

Yes, a calling, you could put it that way. I was called to be this type of doctor. I believe I can bring order to chaos and help people who are in difficult situations in life.

Why is it that many doctors don’t want to do that and say I’m definitely not going to a war zone and running the risk that I’ll come back in a coffin?

Because they’ve got a working brain and are capable of a good risk assessment. You probably need to be a bit disturbed to do it. But then, what about those base jumpers or skiers who speed down a steep mountain a 100 kilometers per hour? I would never do that in my life. I see going into a war zone, where I know the chances of dying are much bigger, completely differently.

Why?

Probably because it makes a difference whether I’m there or not. I’ve never been somewhere where we haven’t been able to change something for the better. I see that a lot fewer people die when we’re there. What’s more rewarding than saving other people’s lives when you risk your own?

As doctors, it’s our vocation, our calling. I completely understand that not everyone wants to risk their families and everything else. If you’d asked me as a 14-year-old boy, I would have shaken my head. Back then, I would never have done anything like this in my life. But the fact that I slipped into it gradually and it always turned out OK, at some point you start thinking you’re…

…invincible?

No, but you feel like nothing can harm you. That’s a bit dangerous. In the First World War, that cost many people their lives. If a soldier charged forth and was the only one to come back, they thought they were untouchable. One day you might not be so lucky, I’m aware of that too. I think you need to have a kind of hubris.

Yet I know a lot of doctors – I’m certainly not the only one – who return to the front again and again. If you ask all these doctors why they do it, you won’t get a clear answer. Some say they do it for themselves, and I do believe that, to a certain extent.

As a sort of mental hygiene, because you want to give something back from your own good life?

In a way, yes. I have a very privileged life. I had a really privileged upbringing. During war, I saw misery on an exponential scale. You see women and children who are truly defenseless. Just a few weeks before, they had a normal life like you and me, and then suddenly everything collapses into chaos and inferno. When you see that, you automatically feel guilty.

I have the ability to help these people. In my role as a doctor, I can heal their wounds, operate on them and help them survive the whole thing. When you’ve seen the massacres I have, helping is no longer just something you want to do. It’s a duty.

When you’ve looked into this abyss, you can’t keep living your life as normal. It’s impossible.

“I look around me like an animal facing a lion.”

Did you come back a different person?

Yes, I’ve got post-traumatic stress disorder, one hundred per cent, which I’m working through. I’m sure of it. Not from my first mission. My first mission in Angola was exciting, even fun. I had my real wake-up call in Rwanda.

What happened there?

We were under constant threat.

You too?

Yes, grenades were thrown into the hospitals, my patients were killed before my eyes. My colleagues were killed. When you see people around you being killed, something happens to you.

How did you survive?

I still wonder that today. Maybe it has something to do with how I don’t panic easily in these situations.

When I’m in a situation where I realize it’s about life and death, everything goes into slow motion. My field of vision shrinks and I focus squarely on it. I shut down and feel as if I’m spending hours considering how I’ll deal with the situation.

I had a similar situation with my daughter, when she nearly drowned in the sea. If I’d gone into a panic, she would definitely have drowned.

By focusing, I can become very calm. I stay still and look around like an animal facing a lion.

As you previously mentioned, it requires a certain emotional distance to deal with extreme situations. Were there moments where you did feel emotional?

Never in a situation where I or the people around me were in danger. I can get very emotional if I’m angry or I sense injustice. Then I need to pull myself together. But never in situations that involve dealing with other cultures or people.

I’ve shaken so many mass murderers by the hand and dealt with some of the world’s biggest criminals, and yet you need to be calm, cool and considered throughout. You need to make compromises so you and your people can work in peace and get out again. Our organizations didn’t hear about a lot of it.

You didn’t need to report it?

Yes, but we often consciously played it down, because we knew we’d run the risk of being evacuated early. Ultimately, they wanted to take us all out of Rwanda, but none of us wanted to leave our posts. We were under constant pressure, the kind you can hardly imagine.

I always say there are two kinds of people I’ve met in my humanitarian career. People who get scared quickly. They pack up quickly and go. That’s a good, responsible thing to do.

And then there are a few people with this hubris who don’t buckle straight away. It’s always the same kind of person, you recognize them immediately. I know I can rely on these people. But in a group of 10, there are maybe one or two.

“It’s not my job to judge people.”

You said you see it as your duty to help. That’s a very honorable reason. But you help everyone, as is your duty as a doctor, which means you also help people who will go on to kill again. How do you reconcile yourself with that?

I’m not a judge. I’m not the person who judges these people. I know far too little about how it came to this.

But you’re also human. And you hate injustice.

Yes, but as a doctor, you can’t show any emotions in this respect. Consciously or unconsciously, in Rwanda, I saved mass murderers’ lives. But it’s not for me to judge. It’s a tough situation. That’s why I never quiz my patients. We just ask what happened. They say they were hit. That’s enough for me. We don’t want to know any more.

You don’t want to have an emotional connection with your patient?

No. But it always happens. I told you the story about the little girl I met in the fire. Among hundreds of bodies and people who have been burned, I met a small child. That was right when I was starting out. I took the child, brought her to a missionary hospital, treated her and, without realizing, developed an emotional connection. I found her so brave and strong I wanted to adopt her and take her home.

Why didn’t you?

Because my boss asked, why this child and not all the thousands of others? That was the first question, and the second was whether I had talked it over with my wife. These two things convinced me. The third thing was: don’t succumb to your emotions, otherwise you won’t be able to keep working here.

And you were able to flick the switch, even though you didn’t know what happened to the girl?

It hurt me. Of course, I also thought of my wife. What would she say if I brought a little girl home with me from Rwanda?

What did she say about it later?

She said: “I would have wanted to be involved.” Of course she would have taken her. She would have reacted exactly the same if I had told the story. She would have accepted it with all the potential issues and complications. After all, it’s not clear what kind of trauma the child would have and when it would erupt again.

But it was absolutely the right thing to leave the child there. I continued to look after the little girl for many years after. At some point, she disappeared. From that moment, it never happened to me again.

From then on, I was a hardcore humanitarian. That doesn’t mean that I don’t have empathy. I have also held children in my arms who lost their parents, taken them chocolate, and comforted them. But that’s all, and no more. It wasn’t like I would have held them every night. There are far too many people who need looking after. You don’t have time for all of them.

“Your tolerance for frustration needs to be extremely high.”

Public appreciation is surely high if you can save many lives like you do. Yet there are probably situations where you don’t have the technical and medical capabilities to help the person properly. What do you do when you realize that it’s beyond you to help the way you’d like to?

Every mission is a constant accumulation of bad experiences and situations. Constant. Ungratefulness, reluctance, wickedness, greed, hate – you’re faced with a great deal of negativity. Your tolerance for frustration needs to be extremely high to do it.

Usually, it starts as soon as you get there. “What are you doing here? You’ve got no business here!” The victims, those who are directly affected, are grateful, but those around them aren’t. You need to resign yourself to that. You need to achieve as much as you can with very little.

You don’t operate in hospitals, I assume, but sometimes right in the field. What are the conditions like?

I’ve performed surgery everywhere. I’ve even done it in stables. We usually try to go to a hospital and not operate in a schoolhouse or stable. In Rwanda, we had a hospital, but it wasn’t any safer or more hygienic than the other facilities.

You have to understand, they have almost nothing. We were delighted if we had at least five to six hours of electricity per day, running water and staff who wanted to work.

The staff also have families who are under threat. Most withdraw and stop coming. We often ended up doing these missions alone. Once I cured my patients, we deployed them as nurses. We were almost recycling people. When we were in Liberia, many relatives and patients helped out in the operating theater. They improvised from beginning to end.

With my work at the front, I’ve experienced a great deal, but I’ve also met so many extraordinary people, like Nelson Mandela in South Africa, a journalist who later became a UN ambassador, presidents, or people in Afghanistan who were on the top 10 most-wanted list at the time. And all simply because you’re the only doctor around for thousands of kilometers.

“My family had to do without me a lot, including at important family occasions.”

But it also seems to me to be a lonely position, because you can’t or mustn’t really talk about a lot of things. For instance, how much can you involve your wife in what you’ve experienced?

My wife has never been faced with it head on. I always wanted to protect her from it, because I was afraid that otherwise, she wouldn’t let me go any more. And she didn’t always want to know, either. She knows me, and she knows I’m not one to say no. So she often simply doesn’t want to know any more in order to protect herself.

Today, I wonder if it might be time to involve my wife more. Particularly as I no longer go straight to the front. Maybe it’s not a bad idea for my wife to see what she’s sacrificed so much for. I missed my daughter’s confirmation because I was operating in a war zone. There are many family occasions where my family have had to do without me.

That’s a high price to pay.

Yes, it really hurts now. Of course, you ask yourself why. Why do you leave your safe environment and risk everything? But I knew my family were well looked-after, while people down there were dying by the minute.

Then I get this feeling of duty, this virus I carry that compels me to pack my suitcase, get out of the helicopter in a scruffy, godforsaken little place and drive the Jeep into the middle of nowhere to help people.

“Does it make sense to stitch together soldiers who will go on to kill again?”

We know that people who have been to war and come back frequently struggle to integrate back into normal life. How do you balance both worlds?

I’ve always been able to maintain this dividing line. First of all, I was never in it for too long. I never did it for years at a time. I always have breaks. So I always come back to normal life quite quickly.

For really tough missions, you needed a certain amount of time to acclimatize. When I came back from Rwanda, I went to work the next day. If I get back to my normal working rhythm quickly, I can resist it somehow.

Then you come back here and make people beautiful. Doesn’t that seem unbelievably banal when you’ve tried to sew an arm back on just a few hours beforehand?

The worst thing is when you feel like you’re wasting your abilities. Then we quickly get to the point where I feel I need to look after my family, and that my family has the right to see me before anyone else.

But to answer your question: when I’m here, that’s my job, and my patients expect the same 150% commitment as the patients in a war zone do. You have to be able to go from one room to another and close the door behind you. You need to be able to adapt relatively quickly to vastly different worlds. I admit that if I were a pediatrician or a trauma surgeon, these transitions would be smoother, and perhaps less…

…striking?

Striking, yes. It would be easier. It’s much more difficult when I hear a patient say they’d like me to take away another tiny wrinkle. Because I’m thinking, yesterday I was standing in front of 20 dead children, and you’re here with your dumb little wrinkle. But they have the right. They’ve paid for it and they can expect a perfect result.

Your two worlds are, to a certain extent, provocative: it’s much harder to see the deeper meaning in cosmetic surgery in comparison to the work you’re doing in war zones.

I don’t really consider this question of meaning. When you weigh it all up, there’s nothing that really means anything. We’re born, at some point we die, and that’s it. Between these two points, people try to give their lives meaning, with the ability and fantastic opportunities our beings and our intelligence permit.

Whether it makes sense to stitch together young soldiers who will then pick up their guns again and kill other people, or whether I give a woman in Switzerland a more beautiful face, which then makes her happy because she looks young and fresh rather than old and tired, I can’t judge. I wouldn’t dare try.

“Like a brothel owner: they’re all happy to come to me, but nobody knows me.”

Then I’ll put it a different way: what’s exciting about cosmetic surgery, a field in which you’re a global leading light?

Changes fascinate me. In restorative surgery, it’s a real challenge to change people so dramatically, even when it’s just their outer shell, that they come as close as possible to the original while still looking as good as possible. I come from a family with a mother who was an artist…

…she was an opera singer…

Yes, but she was also very skilled at drawing. We were all lucky enough to have inherited certain talents. We can draw and got a little bit of her artistic skill. In plastic surgery, I found a symbiosis between my interest in technical and analytical aspects and my interest in esthetics, shape, color, contours.

Of all the fields I worked in, heart surgery, neurosurgery – I’m one of those dinosaurs who still got a very broad education – this was the one that fascinated me.

I had two role models, my two supervisors in reconstructive surgery at the University Hospital in Zurich. They truly inspired me. People with burns had such a strong connection to these doctors throughout their lives. There was always something that needed changing or improving to turn the monster back into a human being. I found this transformation fascinating.

You say you found the personal connection between burns victims and their doctors fascinating. The paradox of your profession: you know everyone, but nobody knows you out on the street, because no one wants to admit they’ve had work done. So you don’t have that connection at all.

No, I always compare myself to a brothel owner. Everyone’s happy to come to me, but nobody knows me. I also tell my patients: don’t be annoyed if I don’t greet you on the street. It isn’t meant to be impolite, but I don’t want your friends or acquaintances to ask, “Are you with Steiger, too? How do you know Steiger?” But I can live with that. We’ve already treated over 40,000 patients.

Where do you get your validation?

From my patients. Although you do get unsatisfied patients, too. You can’t ever please everyone. I’m a perfectionist and the patients expect that of me. But when expectations are that high, sometimes I have to tell them I’m not Harry Potter, I can’t perform magic. I need to follow the basic laws of biology and physics. I’m not a miracle worker. I refuse 15% of patients because I can’t meet their expectations.

Being so selective means 99.9% of patients are satisfied. I can truly say that I find joy in my patients. I know exciting, crazy, fascinating people all over the world. I never would have thought that a little boy from Witikon could have got so far with his career.

“The focus at the front should be on local people.”

You will soon return to a war zone. For years, you’ve been saying that you’d like to have armed soldiers or security personnel with you for protection. How far along are you with that? What’s the current state of play?

We had to change our project a little bit. I realized that we are too far ahead of our time. We set the whole process in motion. We were even with the government. What we realized was: I’d have to put my career to one side and only focus on this project if we wanted to make a go of it.

You need strong partners to support it. The trust of these partners needs to be earned first. We’ve found a back route. If we can no longer be at the front, we need to find other ways we can help people at the front. We asked ourselves: how can we deal with these security situations without aid workers having to risk their lives?

Many people told us to try to find other ways. But even today, I’m still utterly convinced that in a situation like Rwanda, a lightly armed unit would have exuded an authority that could have saved many people’s lives. I also see that the political resistance is so strong that we still can’t make that happen. That’s what we’ve learned in the past few years.

We came up with a new idea. The other approach is that we try with international aid organizations to build centers on the edge of war zones where we can train doctors and treat patients at the same time. Here, neither the staff nor the patients would be at risk.

That would allow us to kill several birds with one stone. We could offer more ambitious medical care, the kind we can’t possibly provide in a war zone because the infrastructure isn’t available. We can’t offer that kind of professional restorative surgery in a war zone. At the same time, we can train doctors from these regions whom we can then send back in. They can then help on the ground.

Help for locals to help themselves?

Yes. My aim with the association is to stop sending “white knights” like me into war zones, who stay for a few months and then leave again. That was always my biggest frustration. We need to start training local people so there’s no need for Steiger any more.

Who takes care of the training?

We do. We’ve developed a concept with a hospital that’s financed by an international aid organization. Together with the American University in Beirut, we set up a partnership that allows us to train medical professionals in an academic environment.

There, they learn how to deal with severe gunshot wounds, what you have to look out for, hygiene standards, what aftercare looks like, how to properly administer anesthesia, how physiotherapy ought to be structured. They get to know the whole chain so they can avoid unnecessary suffering and abnormalities in future through the right initial treatment.

If the trained person then ends up treating injured patients in a little hospital in Aleppo, Homs or Hama, they know that if they apply a plaster cast to the hand properly, the patient will be able to move their hand again in future, preventing them from developing a disability or becoming unable to work. If I treat the burn properly from the start, then I stop the child from becoming deformed and their limbs from ceasing to function.

In future, the focus at the front should be on local people, not foreigners. We have to help them so that they can help themselves in future. This is much more effective and sustainable.

“I don’t want to sneak out of it.”

How far along are you?

The aid organization has been on board for two or three years. We’ve been able to expand the project with their help. Now we’re expanding the training to all fields, so hand surgery, facial surgery, severe facial injuries, burns treatment, bone injuries, soft tissue injuries, microsurgery. We can provide everything a cantonal hospital in Zurich has to offer, on a more modest scale.

We hope we can start this training this year. We’re starting off with small groups and treating the war-wounded from five different war zones.

How do you generate the funds you need?

We’ve started a major fundraising drive, we’re asking major organizations. So far, our idea has gone down very well, particularly because it’s a project that helps people help themselves.

It’s actually astounding that such a training project doesn’t already exist.

Yes, we have three young orthopedics specialists from Syria and Lebanon who’ve been with us for three years. They’re already so good that in two years’ time, they’ll be able to take over the center themselves. Our aim is to hand over this project at a high level in five years.

The doctors understand that if a war breaks out in their region, they can move the hospital to another region and carry on with patients who can be moved. There are doctors on site who are familiar with the language and culture. They know exactly how to conduct themselves. The risk of something happening to them is much smaller.

So we’re creating a pool of doctors we can deploy across the entire region. If the concept of “restorative surgery” works, hopefully in two or three years, we’ll be able to expand it to other medical specialisms, such as pediatrics, gynecology, obstetrics and so on. We want to set up a humanitarian hub for surrounding war zones.

Where exactly?

In Lebanon. We’ve already come very far there. We’re already treating patients from Syria, Yemen and other war zones. I’m traveling back to these areas soon to recruit new patients in refugee camps and border areas. We’ve been setting this up for two-and-a-half years.

It sounds like a reasonable succession plan. How long will you continue to work at the front?

If I stay as fit and healthy as I am now, I hope I can do it for at least another ten years.

So you aren’t minimizing the risk of being killed on one of these missions.

No, I don’t want to sneak out of it. What we want to achieve with this project in Lebanon is being able to return to the field and go to the front. Hopefully, our protection idea will be given a chance there. We have this pool of people who are going to give us the political heft.

We even hope to get support from a big software company, which I can’t yet name but which everyone knows and uses every single day. They want to develop software for us so that we have access to secure communications, meaning our staff can send us pictures of patients from the field and ask us how to treat the patients, and we’ll even be able to give them instructions using this technology.

Interestingly, in every conflict, mobile phones work everywhere. People can then even press a panic button if they’re under threat. You see, if we have something like that, it’s no longer just a vision. We’ve got something tangible and practical that works at the front.

So your wife can’t look forward to peacefully living out her twilight year with you?

She told me that she doesn’t want to have me at home all the time. She wants me working on something. She says I’m unbearable when I’m sitting around the house.

Written by: Anna Maier

Images: Jean-Pierre Ritler

Anna Maier in conversation with Enrique Steiger.

Newsletter

Subscribe to our newsletter and you'll get notified every time a new article is online.