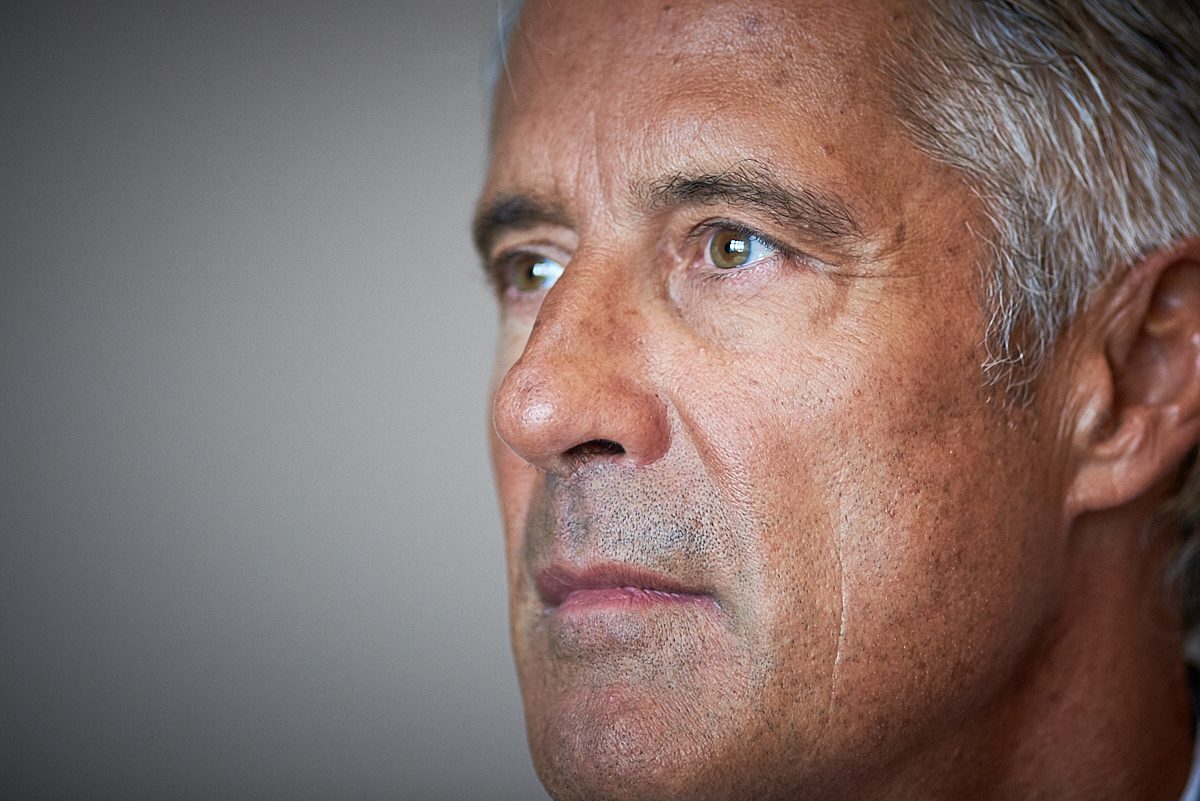

“I want to suffer a little.” Michael von Hassel, photographer

His pictures are just like his life: extreme and intense. How he takes them, too: in Siberia, North Korea, and the Caucasus. Why he goes in search of isolation rather than taking photographs of people, why he could no longer meditate after his father’s death, and what frightened him on his trip to North Korea.

There are moments in life which are so different that they attract our attention. When you’re surrounded by people, it’s loud and hot and somehow you’re overexcited by the constant stimulation, and a little ray of light appears.

I had a moment like this, almost 13 years ago, at a German charity event, “Tribute to Bambi.” It might sound a little dramatic, but the man who suddenly appeared before me looked like a prince, with his blond curly hair and his dapper clothing. We had a brief encounter as we ordered drinks at the bar.

Although we didn’t make conversation, let alone exchange our names, the moment stuck, and we met again online weeks later. We struck up a casual friendship, dropping each other a line now and then.

I learned that he came from an illustrious family. His great-uncle was Kai-Uwe von Hassel, who had been president of the German Bundestag. Another of his forebears was the Count of Tilly, whose larger than life statue can be found in Munich’s Feldherrnhalle. So there are other members of the family who are also mentioned in the history books.

Michael von Hassel in front of one of his forebears, Johann T’Serclaes von Tilly, Feldherrenhalle Munich, Germany

It was the expected academic career path that Michael von Hassel took initially, becoming an economist, taking a brief detour to London, where he worked with millions as a banker, until he quickly realized: “it was hardly Bohemia.” He became an artist. A collector snapped up his entire first show in a Berlin gallery before the preview even took place. A lucky man.

We met each other here and there, whenever our paths happened to cross: most recently at the 2009 “Hot Art Fair” in Basel, when he received the Hot Art award for “Best Contemporary Artist.”

When we meet again in his Munich studio for this interview, Michael von Hassel, 40, tells me that this award was linked to a terrible event.

Von Hassel in front of his art piece at restaurant Tantris, Munich

“It’s just too soon for me to let go.”

Michael von Hassel: My father died on the very same night I won the prize.

Anna Maier: Oh, no …!

I called home. My parents were sitting with some friends on the terrace, then my dad went upstairs and dropped down dead. That was it. That changed so much for me. It was only then that I realized: in life, there’s no such thing as safety. But I draw a lot of strength from this sense of insecurity now, too. I can do everything and be anything, because there’s no such thing as safety.

What has changed since your father’s death?

Well, there’s this restlessness. I used to meditate a lot. I was able to get into a state where all these crazy thoughts would suddenly stop for about ten minutes. Not any more.

And what are you doing to combat this? Don’t you want to be able to get back into that state?

It’s just too soon for me to let go. I think I want to suffer a little, too.

Is that the lot of the artist?

I don’t know. But it’s my lot. It’s brutally hard for me, because we were similar in so many ways. I often think of moments that make me sad somehow, because of something I didn’t do.

“That’s why I want to live and do all these crazy things.”

For instance, I was in LA once for a series on vintage cars, and there was a white Rolls Royce with white leather seats and white wheel trims. My father said: “Buy it, and we’ll drive it from the West Coast to the East Coast and bring it to Germany.” I asked how much it cost, but at $5,000 it was too expensive for me, because I had seen you could get it cheaper in Germany.

Today I ask myself, why didn’t I buy it? How funny would it have been to have a breakdown in this crappy car somewhere in the Nevada desert (laughing)… in the white Rolls Royce with my father. So that’s why I want to live and do all these crazy things.

How were you similar, you and your father?

He was the one who taught me photography. From my great-grandfather down, all of the men in my family took photographs. I’ve even got some of his cameras.

Are you carrying on the family tradition?

With one difference: none of them were professional photographers. No one did it for money. But they all spend a crazy amount of money on photography equipment and traveled far and wide. To German East Africa, now Tanzania, around 1900. They had farms there.

Traveling there was totally different then to how it is now. So I see a little of myself in that tradition too. I’m in search of the last little adventures you can have on this planet.

“When a person is left completely on their own, they don’t know any borders or nationalities.”

Did you always have this adventurous gene?

Adventure is a quite a big word. I just want to have seen the world. Last year, I was in North Korea. In June, I’m going to the Caucasus. I always want to be on the move, to form my own opinion of what it’s like in a place and to meet the people who live there in person. Where does that come from? My grandfather told me a story:

he was a private in the army, and he was at the siege of Leningrad. It was winter and they had a sort of timetable for shooting. When they had free time, one day a week, they would always go to the frozen lakes, make a hole in the ice and use rods they made themselves to fish, so they had something to eat.

Eventually, he ran out of bait. So he went up to a Russian soldier who was sitting there, said “hello,” and asked him – using his hands and feet – whether he could lend him some bait. Which he did – and gave him a gulp of his vodka into the bargain.

A week later, they met again at the frozen lake and the Russian said: “why don’t you make your fishing hole here next to me?” From then on, they always fished together.

And that’s how people are, aren’t they? When a person is left completely on their own, they don’t know any borders or nationalities. I am convinced that it would help us all if we would all visit each other more.

“I form my own opinion before I absorb someone else’s.”

For instance, I hadn’t been to Poland until three or four years ago. So I took a big trip to this neighboring country and a very, very close look at it. Today, in the political discourse, there is so much anger, so much misunderstanding, so much strangeness, once again. And you wonder, with the history we have with each other, or between each other, how something like that could ever happen again. Why?

So I go there, I take a look and I form my own opinion before I absorb someone else’s. And it’s exactly the same for North Korea. Because when you change your point of view and put yourself in the other person’s shoes, then you’ll understand so, so much about what leads to conflict resolution.

What did you learn about in North Korea?

Well, the history, for one thing. Did you know why North and South Korea are separate? Korea, the whole of Korea, was occupied by Japan for sixty years before the Second World War. For time immemorial, Korea was invaded again and again by all of its neighbors. By the Russians, the Manchurians, the Han Chinese, the Americans in any case, the Japanese. So they are essentially cautious and a little bit sensitive when it comes to their neighboring countries.

After the Second World War, Japan was completely besieged by the Americans. So the Koreans thought: now we’re on the winning side! After all, my enemy’s enemy is my friend. So a delegation of officials went to Washington and wanted to discuss the future of a united Korea with the US president. But nobody listened to them. Instead, they made common cause with Russia and the UN and just divided Korea up.

“It’s probably the place with the strongest surveillance and the most weapons in the world.”

Now, you can understand a little bit why Germany was split up, quartered even. We did start a massive war, after all. But Korea never did anything to anyone. On the contrary: they were terribly exploited by the Japanese for sixty years. And many of the women were made into sex slaves for Japanese soldiers. The men were killed in the mines.

What happened to the country was truly awful. The USA and Russia – with the help of the UN – simply divided the country up between them, just because they could, because they wanted a slice of the pie, too. And they did it along a border, a sort of administrative border, that the Japanese had already drawn: the 38th parallel north.

What’s there? Is it a barbed wire fence? A wall?

It’s a minefield. There’s an incredible number of barbed wire fences, and a minefield. It’s probably the place with the strongest surveillance and the most weapons in the world. There are huge armies on both sides, ready to strike.

“It’s an atmosphere that’s indescribably dreadful.”

Can you go there at all?

You can get there from the north if you manage to take part in a tour program. But it’s not always straightforward, because they change the program almost by the minute. It’s much easier to get there from the south. There’s a place, a hut, where North Korean soldiers are on one side and South Korean soldiers on the other. They stand in the same space and stare at each other. All day long. In theory, it’s a border crossing, but in reality, it isn’t at all. On the South Korean side, there are huge loudspeaker systems that send messages to the North, in the hope that some North Koreans might hear them.

What did you take away from this journey?

Oh, I took away a lot for myself. First of all, I just wanted to take a look at this country. It’s so different from everything we know. I wanted to have experienced it. A friend I met in Vladivostok said: “we go to North Korea when we want to remember how bad everything used to be. When half the world was in that state.” The Eastern bloc. And it still exists there. Total surveillance, a total lack of freedom. It’s an atmosphere that’s indescribably dreadful.

Did you experience that too, then?

Yes. I was there for ten days. A lot happens to you there, too. Mainly two things in particular: at the beginning, you still think, I’ve got my German passport here, I’ll just move on. Or: if they’re weird with me, then I’ll just fly out.

“There’s a camera up on the ceiling. And it’s trained on your bed.”

And then these things happen. Your guide says to you: “Michi, you still haven’t called home. You should call home. There’s a phone in your hotel room.” The next day he says it again: “You still haven’t called home! Call home.” So I think, OK, I can actually call my mom and tell her that I’m fine. So I put the receiver to my ear and then there are these crackling sounds like in a bad spy film. So I ask my mom: “can you hear this crackling the whole time too? Crackling like in the films. Crackling!” Hoping she doesn’t say anything wrong on the phone.

You couldn’t send her a WhatsApp in advance to warn her, because there’s no Internet there.

You’ve got no Internet. You can keep your phone, but it doesn’t work. Then you lie down, look around your hotel room and you see it: there’s a camera up on the ceiling. It’s a tiny camera. But it’s there. And it’s trained on your bed. So you try to pull the table away from the wall and put it underneath so you can climb up.

Didn’t work?

The table is screwed to the wall. You get these little pinpricks like that the whole time. And every day, another little thing happens. Suddenly, you’re frightened: I’m not safe here with my German passport. I’m not safe at all. Then another couple of things happened to me. For instance, when we were at the ski resort they’ve built there. We went there to ski. The most absurd moment of my life.

“Soldiers taped away the ice by hand.”

Why?

They built this ski resort by hand, with huge masses of people. They didn’t drive the heavy truck up the mountain. Instead, hundreds of them pushed the truck up the mountain. Maybe they were trying to save on gas? They diverted rivers by hand. And absolute poverty is all around.

The journey to the ski resort takes a whole day. On an unbelievably wide road that’s peppered with potholes. There are almost no cars to be seen for hundreds of kilometers. On the road, the ice was pristine, rock hard, and five centimeters thick.

But unlike in central Europe, no one had sent a gritter early in the morning to make the road passable. They sent 2,000 soldiers onto the road to tap away the ice by hand, using knives, hand-made sticks and shovels.

“Who was in room 651?”

And what happened on the trip?

An acquaintance of mine wrote a big piece on Spiegel Online about my journey through Siberia.

It had just been published, and I wanted to thank her in some way. In the hotel there was a really beautiful, well-made brochure, an advertising brochure for the ski resort and the hotel. And I thought that would be a great souvenir for her, since she works in the Travel section at Spiegel. So I grabbed it.

On the day we left, our buses didn’t start and we sat in a snowstorm for quite a while. There were 60 of us, in three vans. The snow was getting worse and worse and we were trying to get to the capital. Instead, we were just sitting there. We all wondered why we weren’t traveling.

Suddenly, the hotel manager came out and talked to our main travel guide. Then he got on the bus and announced on the microphone: “Who was in room 651?”

And that was you?

That was me. Oh God! I thought, what’s this all about?! “A hotel brochure has been stolen.” We all knew the story of Otto Warmbier, the American who tore down a poster and was sentenced to 15 years in a North Korean labor camp.

“Of course you’re frightened. You get real spooked.”

So I said: “No, no, it’s a publicity brochure. It’s advertising, it’s meant to be taken! I wanted to advertise for you in Germany.” Then came the reply: “the concept of ‘advertising’ doesn’t exist in North Korea, so it’s theft.” It was as if I was rooted to the spot: “I can give it back right away! I didn’t mean it that way, it was a misunderstanding. I’m so sorry.” Then I jumped out to get my suitcase, rummaged for the thing, and cleaned it up. Then I gave it back to the hotel manager with a deep bow, apologized again and he said – in German! – “it’s OK,” turned around and left. The secret service agent went with him.

After ten minutes, he came back out of the building and had the brochure with him again: “Here, a gift. I bought it for you, for ten euros.” I think: oh God, ten euros! That must be, I don’t know, three months’ wages for him, or more. When I pull out the money and try to pay him, he turns it down flat: “No! Don’t insult me! It’s a gift!”

Is this kind of situation frightening?

Of course you’re frightened. That’s exactly what happens to you. You get real spooked.

And the second thing that happens to you in a country like that: they’re working on you every day, 24 hours a day. They’re always chatting, all of them, behind you, in front of you, telling you how great everything is. Propaganda in its highest form. You start to absorb it quite quickly. Eventually, you stop thinking it’s so bad. And only when you get some distance and you think about it again, about this and that thing that happened, you notice: “It’s totally absurd that I didn’t think it was so bad. How can that be?”

“You’d wonder, who is that?”

Were you able to take photographs freely of whatever you wanted?

Yes and no. They were always saying: “no pictures here!” For reasons that were either explained to us or not at all. Now and then, I’d take a picture of something and then someone would come and take the camera away or keep it shut and say: “not that!” although somebody had said before that I could.

Sometimes it was our people, and sometimes it was people we didn’t know, who were simply walking along the street and looked like passers-by to us. Suddenly someone would come over and say in German: “you can’t do that!” You’d wonder, who is that? Why is he running up to me from back there at the other end of the square and saying something to me?

How far does your risk-taking nature go?

It’s growing. Which I find astonishing. But I just think it’s important to experience these things and to be able to tell people a little bit about it. And to promote the idea of communicating with each other. I got a lot of criticism for traveling there, too, because I would be supporting the system with my money. Well, ten days, with flights, all the food and every glass of beer, cost €1,700. It didn’t cost the earth, did it?

On the other hand, I had a plan. It was clear to me that I was only meeting people who thought the system was good and that the stories they told me took that line. But they were still people, too. I decided to ask really normal questions like: “where do you get new clothes? There are no shops here. Not a single one. No clothes shops, no department stores, no restaurants. How does it work?” Then they’d explain to you: “Yes, we regularly have a clothes day at the company where we work, or at the office or the ministry. You get allocated clothes there. The same things happens in school.” And then they just get two new shirts maybe once a year, and a jacket every three years, and a pair of pants every five years, and a winter coat every seven years.

“The Koreans always immediately stopped the conversation as something became uncomfortable for them.”

What I hoped for – and what sometimes happened – was that someone would ask a question in return. How do I get new clothes? And then I’d explain how we did it: in our country, you go downtown, and in bigger towns there are lots of shops. For colorful clothes, gray, black, expensive, cheap, clothes for tall people, small people, fat people, thin people… And if we can’t find something anywhere, you can go online too, on your phone or computer. You can order anything under the sun. And then it’s delivered to your house in a few days.

The Koreans always immediately stopped the conversation and left as soon as something became uncomfortable for them. But I hoped that just this conversation between us in itself set something off. Maybe they take something away from it. And maybe that brings about some kind of change. Hopefully for the better.

“I want to have this place just for me. People only disturb it.”

You’re a very communicative person. You find it easy to speak to strangers. You find a personal connection. You were predestined to take pictures of people. Why don’t you like doing it?

I can tell you why: because my life is already very sociable. I only take pictures of a percentage of it, actually. And there I just want to enjoy my peace and quiet, find some distance and be alone with my thoughts. I want to have this place just for me. People only disturb it.

Do you sometimes picture what you would still like to achieve?

No.

No? Really?

Nah. I don’t really want anything. I don’t need anything either. I don’t need any status symbols, I don’t need a fancy house, I just need less, less of everything… What I would love is a peaceful little place, far away in the mountains, totally unspectacular, with an herb garden. That would be something.

“It would be great to leave something in the world.”

Or another dream I have: there’s a legendary place in Munich called Schumanns. There’s a big bar there, with an empty wall. I would just love to take a photo of Schumanns that could hang there. But I respect it too much for that.

But why there? Is it just the empty wall that’s crying out for you to have a picture there?

I wanted to be an architect when I was a kid. I thought it would be great because you could just leave something in the “world” for a few minutes. A little of you is left behind when you’re no longer there. And I think it resonates a little when you immortalize yourself in this kind of place.

But for me, it doesn’t have to be in a MoMa in New York, just a cozy bar. I find that much more valuable. I think it’s great that you can be in a place where all kinds of people enjoy spending their evenings. I think that’s great. But nah. Apart from that, I don’t have any dreams.

Images North Korea: Michael von Hassel

Newsletter

Subscribe to our newsletter and you'll get notified every time a new article is online.